Springsteen steps out of the Darkness

25-09-2010 The Irish Times par Shane Hegarty

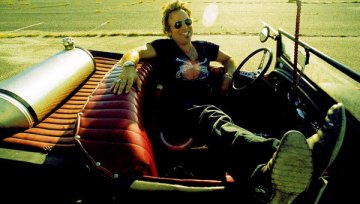

AN ITALIAN RESTAURANT on a calm street in downtown Toronto. Bruce Springsteen sits on the inside of a long table, his back to the wall, the focus of such attention from the group lunching with him, who are leaning in towards him, that it would be understandable if the singer asked everyone to just back off a bit. He doesn’t. He talks on, answers every question and indulges those trying to hog the encounter, while making sure to address those at its edges. The cluster of record executives and journalists are all male, except for a Japanese woman whose colleagues manoeuvre her so that she’s directly to Springsteen’s right. Thereafter she sports the stunned grin of the starstruck. It’s a popular look among those around the table. A waiter stops mid-service to earwig and is still there 15 minutes later. Already, Springsteen’s wife and E Street Band member, Patti Scialfa, has volunteered to be squeezed from the table: “I’m going to move out to let you guys get closer to him.” She does it with the generosity of someone who knows that some of us are in the thick of fulfilling a lifetime ambition. I won’t pretend I’m not among them. That Springsteen has joined us is something of a surprise. He is in town because of Toronto International Film Festival and the premiere of a documentary about the making of Darkness on the Edge of Town, which itself comes in advance of The Promise , a box set comprising an album of other songs recorded for that session, plus new and old live footage and the documentary. That year-long Darkness session, 32 years ago, off the back of a legal battle with his first manager, spawned dozens of songs. Some were half-finished, others dropped just as they were done, so that what Springsteen calls the “10 toughest songs” remained – including the title track, Badlands , The Promised Land, Racing in the Street, Factory, Streets of Fire – hewn from a session that drove the E Street Band “a good deal insane”. Springsteen spent weeks alone just trying to get “the drums to sound like drums”, as the documentary explains. While sonically sparse compared with the previous Born to Run , Darkness on the Edge of Town is an epic of American landscape, dispossession and resilience born out of a “huge amount of ego, ambition and hunger”. He wanted to write something truly great. It wasn’t greeted too keenly by much of the press. It didn’t sell too much at first either. Then he toured it. “When they saw it live, then they got it,” he says. Today it is a classic. When he was recording it he was doing so with the intensity of a musician who didn’t know if he’d get another chance to make an album once this one came out. At a time when a three-year gap between albums was career suicide he read “where are they now?” pieces about himself. “We were dead,” he says, with a certain relish. “They just wanted to know if it was real or if it had been a construction.” So he focused on writing “the most important album we could, the biggest thing ever”. When Darkness was released Dave Marsh, in Rolling Stone , declared it an album that would change the way people listened to rock. In The Irish Times , Joe Breen said it confirmed him as “the most important songwriter in rock” – but not all reviews were so positive. “It wasn’t Born to Run 2, so they didn’t get it,” says Springsteen. Then he took it on the road. “In one town,” he says, “this kid comes up to me and says, ‘Hey, Bruce, my friends say it’s not as good as Born to Run , but I think it’s okay.’ ” Earlier in the day about 40 of us gathered in an old cinema where some of the “lost” tracks and concert footage were introduced by his manager, Jon Landau, whose 1974 quote “I saw rock’n’roll future, and its name is Bruce Springsteen” we are at this point obliged to reference. Verses appeared on the large screen in time with the songs. The first track was not one that had been lost as such but a version of Racing in the Street that was so lush it was like hearing it for the first time. When it faded out someone behind me gasped quietly. They’re record executives, of course. They’re paid to gasp. But, hell, through surround sound, with Panavision lyrics, in the soft hush of the cinema, it was goosebump stuff. Seven more tracks were played, revealing a range of songs, with a more pronounced interest in love and relationships than present on the original album. There are some live clips from the DVD element of the box set, including a live recording of Darkness , in correct order, during which Springsteen is in full flight, neck straining, teeth gritted, making no concession to the fact that it is being recorded in an empty theatre. After this Landau returns to his mic in the corner of the room. A spotlight struggles to keep up with him. He thanks a few of the people involved. Then he thanks Springsteen. He is sitting at the back of the theatre. The man behind me gasps again. Springsteen gives a modest wave. He gets a standing ovation. Twenty minutes later Springsteen and the cloud of people that gathers around him have been ushered from the venue for a restaurant next door. Small groups are brought to his table intermittently. Our turn comes, and we move up, glasses of wine where autograph books might be. It is just after the starters, and we spend the rest of the meal with him. For the journalists in the group it is a strange set-up: not an interview but not off the record. Throwing a Dictaphone on the table would change the dynamic. He talks about survival, success, his memories of whichever country someone wants him to talk about. He talks about the way modern culture expects you to be ubiquitous. “They think I’m a recluse, that I never do any interviews,” he says. “I do interviews all the time. I think I’m pretty accessible. But if you’re not always out there, they think you’re Garbo.” His presence in Toronto has been the focus of media coverage during the week. At a festival that cultivates queues regardless, the one for a Q&A with the actor Ed Norton began the night before. At that event, his voice a low rumble to Norton’s halting helium, he had talked mostly about Darkness on the Edge of Town , his “angry” record, informed primarily by his wish to write about his parents’ generation and their struggle to match the promise of the US with its reality – “honouring my parents and their history and the people I knew: these things weren’t being written about” – and to reflect the post-Vietnam era and his country’s loss of innocence. Artistically, it was influenced by the attitude of the punk movement, by movies such as Mean Streets and by Springsteen’s travels across the US, which took him out of New Jersey for the first time and sent him into an epic landscape that can be heard on the album. But most of all it was about reclaiming something of himself, post-fame. “I had my first taste of success, and I think you realise it’s possible for your identity to get co-opted,” he says. “When you have some success you have a variety of choices. I looked at some of the maps the people before me had drawn. ‘Here there be dragons!’ And the world was flat to them, and they fell off the edge. And that was something I’d rather not do. And part of that was keeping a sense of myself.” He became “a mutant in your neighbourhood”. “I decided that the key to that was maintaining a sense of myself, understanding that a part of myself had been mutated . . . There was a thrust of self-preservation more than anything else.” In the restaurant it is palpable how much he has built an inner circle, and fortified it over decades: Landau and co-manager Barbara Carr; the same record company; the core of The E Street Band has remained largely unchanged since the early days. He talks about this unit, how the film-maker Thom Zimny has become part of a crew that “go beyond committed” and a band who have to stay so in order to fulfil the stated mission. In a politically polarised US he is now as big – probably bigger – outside his home country. Even among the committed, the reaction in the US doesn’t quite match that he receives in Scandinavia, Italy, Spain and Ireland. Landau had said it earlier, Scialfa backs it up over lunch, and Springsteen adds to it. “They just bring such a passion with them, and you feed off that,” he says, but without the emptiness that usually comes from praising one or other country’s audience. Seven years ago he played a single show at the RDS. Over 2008 and 2009 he played five. I wonder if there was a cementing of that relationship during the Seeger Sessions tour in 2006, when the folk-heavy music was appreciated here on a level not matched elsewhere. “No,” he says, “it was on Devils Dust . I came and played the Point, and I thought I’d love to just do 10 of these shows. There was an intensity about that show that was powerful.” There was indeed, aided by the fact that it was raining so hard that the drumming on the roof offered an atmospheric duet during what was a solo performance. The audience intensity is, though, a response to his own commitment on stage. He has toured relentlessly in recent years – 11 shows in Ireland alone since 2005 – and last time around he was playing almost three hours of bone-shaking brilliance without even the pretence of walking off for an encore. “You have to want to do it,” he says. “Also, you have to show, not tell. That’s why they call it show business. It’s not the ‘tell business’, it’s ‘show’ business’ ” He talks about Sting once telling him, “You work too hard”, then later adding: “Oh, I get it, this is the only way you know how to do it.” Springsteen’s drive has to be matched by the band’s, and he will not allow it to flag. “I would put any of our shows now alongside anything we did 30 years ago,” he says. “I want it to be that if your brother comes to see this, he won’t have seen us play better. If your father comes, he won’t have seen us play better. If you’re grandfather comes, he won’t have seen us play better.” Since the turn of the decade he has become fascinated by his own past and is keen to catalogue it. “I’ve become interested in the history of the band, in putting it together,” he says. “For a long time I was u ncomfortable about filming, but about 10 years ago we decided to film everything. And this is about putting things together for all of those who are new to us, who have come to our shows and started listening to us but who weren’t even born when Darkness first came out.” Two years ago Born to Run received the box-set treatment, but what makes Springsteen so vital is that he has not turned to the past in the need to remind the world of his relevance. In his producer Brendan O’Brien he has found a steady hand on recent albums, but the core has been Springsteen’s creative purple patch. His most recent album, last year’s Working on a Dream , was in some ways a sigh of contentment after previous albums that were politically charged ( Magic, The Seeger Sessions ), intimate ( Devils Dust ) or spanning both personal and public grief and resilience ( The Rising ). Although even Working on a Dream was an exhalation of relief, following Barack Obama’s election. His music, he says, has always been a search for what he calls the “essential”, that element that gets to the core of everyone’s experience, “that essential thing that matters to me, that matters to him, that matters to you”. He has stuck with Martin Scorsese’s line about getting an audience “to care about your obsessions”. Darkness was the beginning of what he calls the “long narrative” of his songwriting, a story he began to tell with it and which he has committed himself to carrying through everything since. The night before, he had told Ed Norton that he always understood this necessity. “I said there’s other guys who play guitar well, there’s other guys who front really well, there’s other rocking bands out there. But the writing and the imagining of a world, that’s a particular thing, you know. That’s a single fingerprint. All the film-makers we love, all the writers we love, all the songwriters we love, they put their fingerprint on your imagination, in your heart. And on your soul. That was something that I felt touched by, and I thought, well, I wanted to do that.” It has meant that his themes have been not just political or societal but very personal. He writes, after all, about ageing in a way that few other artists are brave enough to do. There has to be a commitment to that, he says. He must be unflinching, must not shy away from saying that people change and age, and that you have to deal with it. “Write about it,” he says. “Don’t be scared of it.” When recording the Darkness live set he demanded that the decades be on stark display. He found a way in an unlikely source. “I saw this Jean-Claude Van Damme movie. I don’t know if you’ve seen it: it’s called JCVD , and he plays himself in it and gets caught up in a bank robbery. But it’s filmed in this washed-out way, very grey, and it really shows his age. And I said to Thom, that’s what I want for this recording.” Springsteen turned 61 on Thursday. He is tanned, fresh; even the crow’s feet are taut. His hair is dark enough that you wonder if it might be dyed, but grey splashes about his ears. He has an enthusiasm that seems to bubble through from his 27-year-old self, a wick of youthfulness that burns through. It becomes clear that, over the course of a couple of days, Springsteen has returned more than once to the notion of survival, of Darkness being recorded with an intensity born of an understanding that this could have been the last album he recorded. Stunted by the legal wrangle with his manager, Springsteen had to survive on live shows and the reputation of Born to Run . That album had made him a global star and was the thing that put him on the cover of Time and Newsweek in the same week in 1975. In a sense, it had the power to kill him too. From this perspective Darkness is integral to the flow of his career, but from his own viewpoint at the time it could have been the end. He expresses deep pride at the result, how it sounded then, how it sounds now. But it is also becomes clear that his open excitement is from a keen appreciation that he is not just revisiting an album, a session, some old video footage, that this is not merely a holiday with nostalgia, but that he is revisiting a fork in the road with the satisfaction of knowing that his younger self chose the right path. The lunch ends. Springsteen’s meal has been half-eaten, accompanied by a largely untouched glass of orange juice. He has to be encouraged to leave for his flight. Ten minutes later a photograph is posted on Twitter by someone who lives by the restaurant. It is of Springsteen, in check shirt, jeans and sunglasses, with a huge grin, sitting on a motorbike on the street, posing with a fan. It is making someone’s day. You’d be hard pressed to tell whose. |

Springsteen sort de l'obscurité

Un restaurant italien dans une rue calme du centre de Toronto. Bruce Springsteen est assis à une longue table, adossé au mur, mobilisant l'attention de tout le groupe qui mange avec lui, qui se penche vers lui au point qu'on pourrait comprendre que le chanteur leur demande de reculer un peu. Mais il ne le fait pas. Il parle, répond à chaque question et cède à ceux qui essaie de monopoliser la rencontre tout en s'assurant d'être entendu par ceux qui sont sur les cotés. Le petit groupe de professionnel du disque et de journalistes sont tous des hommes, sauf une japonaise que ses collègues réussissent à placer directement à droite de Springsteen. Aussitôt elle abore un sourire ébahi d'admiration face son idole. Et il y en a d'autres parmi ceux qui sont autours de la table. Un serveur s'arrête pendant son service pour tendre l'oreille et 15 minutes plus tard il est toujours là. Déjà, la femme de Springsteen et membre du E Street Band, Patti Scialfa, s'est portée volontaire pour se retirer de la table: "Je vais aller dehors pour que vous soyez plus près de lui". Elle le fait avec la générosité de quelqu'un qui connaît que parmi nous certains sont en train d’accomplir l'ambition d'une vie. Je ne vais pas prétendre que je n’en fais pas partie. Que Springsteen se joigne à nous est une peu une surprise. Il est en ville pour le Toronto International Film Festival et la première d'un documentaire sur le making of de Darkness on the Edge of Town, elle-même avant-première de The Promise,un coffret contenant un album d'autres chansons enregistrées pendant cette session, plus de nouvelles et d'anciennes images live et ce documentaire. Cette session Darkness d'une année, il y a 32 ans, après une bataille juridique avec son premier manager, a engendra des douzaines de chansons. Certaines à moitié finies, d'autres jetées aussitôt terminées, pour ne garder que ce que Springsteen appelle les "10 chansons les plus solides", dont la chanson titre,Badlands, The Promised Land, Racing in the Street, Factory, Streets of Fire - engendrées à partir d'une session qui a poussé le E Street Band vers "un truc de dingue". Springsteen a passé des semaines tout seul just pour essayer d'obtenir des "batteries qui sonnent comme des batteries", comme l’explique le documentaire. Bien que moins copieux sur le plan du son à comparer avec son prédécesseur Born to Run, Darkness on the Edge of Town est une épopée en paysage américain, dépouillement et résilience née d'une "énorme quantité d'égo, d'ambition et de faim". Il voulait écrire quelque chose de vraiment grand. Ca n'a pas été très bien accueilli par la presse. Au départ, ça ne s'est pas très bien vendu non plus. Il est alors parti en tournée avec. "Quand ils ont vu ça live, alors ils l'ont apprécié", raconte-t-il. Aujourd'hui, c'est un classique. Quand il l'a enregistré, il l'a fait avec l'intensité d'un musicien qui ne savait pas s'il aurait une autre chance de faire un album une fois celui-ci est sorti. A cette époque où un fossé de trois ans entre deux albums était suicidaire pour une carrière, il lisait des articles sur son compte du genre "où sont il maintenant?" "Nous étions morts", raconte-il, avec une certaine délectation. "Ils voulaient juste savoir si c'était vrai ou si c'était une posture". Alors il s'est focalisé sur l'écriture "du plus important album qu'on pouvait faire, le plus gros truc". Quand Darkness a été publié, Dave Marsh, dans Rolling Stone, déclara que c'était là un album qui changerait la façon dont les gens écoutent du rock. Dans The Irish Times, Joe Breen a dit que ça le confirmait comme "le plus important auteur de chanson rock" - mais toutes les critiques n'étaient pas si positives. “Ce n'était pas un Born to Run 2, ce qu'ils n'acceptaient pas" explique Springsteen. Il est alors parti sur les routes avec. "Dans une ville", raconte-t-il, "un garçon est venu vers moi et m'a dit, 'hé, Bruce, mes amis disent que ce n'est pas aussi bon que Born to Run mais moi, je pense que c'est bien' ". Plus tôt dans la journée nous étions environ 40 réunis dans un vieux cinéma où une partie des pistes "oubliées" et des images de concert nous ont été présentées par son manager, Jon Landau, dont nous nous devons d'évoquer à ce stade la citation référence de 1974 "J'ai vu l'avenir du rock'n'roll, et son nom est Bruce Springsteen". Les couplets sont apparus sur l’écran en même temps que les chansons. Le premier morceau n’est pas un titre qui s'est perdu en tant que tel mais une version de Racing In The Street qui était si luxuriante qu'il nous semblait entendre ce morceau pour la première fois. A la fin du morceau, quelqu'un derrière moi a doucement le souffle court. Ce sont des professionnels du disque, bien sûr. Ils sont payés pour avoir le souffle court. Mais, bon sang, avec son surround, avec des paroles Panavision, dans le silence feutré d'un cinéma, il y a de quoi avoir la chair de poule. Sept autres titres ont été présentés, révélant un éventail de chansons avec un intérêt plus prononcé pour l'amour et les relations que sur l'album original. Il y a des extraits en directement issus du coffret DVD, y compris un enregistrement live de Darkness, avec les titres dans l'ordre, au cours de laquelle Springsteen est à son meilleur, cou tendu, dents serrées, sans concession sur le fait qu'il est en cours d'enregistrement dans un théâtre vide. Après cela, Landau revient à son micro dans le coin de la pièce. Un projecteur a du mal à le suivre. Il remercie quelques unes des personnes impliquées. Puis il remercie Springsteen. Il est assis à l'arrière du théâtre. L'homme derrière moi a de nouveau le souffle court. Springsteen esquisse un geste en toute modestie. Il reçoit une ovation triomphale. Vingt minutes plus tard, Springsteen et la nuée de personnes qui s'est rassemblée autour de lui ont été conduits de la salle à un restaurant situé à côté. De petits groupes se sont conduits à sa table à tour de rôle. Notre tour arrive, et nous avançons, à la main un verre de vin au lieu d'un carnet d'autographes. C'est juste après l'entrée, et nous passons le reste du repas avec lui. Pour les journalistes du groupe, c'est une étrange installation: pas une interview mais pas de "off". Sortir un dictaphone sur la table risquerait de modifier la dynamique. Il parle de survie, du succès, des souvenirs de n'importe quel pays si quelqu'un veut qu'il en parle. Il parle de la façon dont la culture moderne exige de vous d'être omniprésent. «Ils pensent que je suis un solitaire, que je ne fais jamais d'interviews, dit-il. "Je donne interviews tout le temps. Je pense que je suis assez accessible. Mais si vous n'êtes pas toujours là, ils pensent que vous êtes Garbo." Sa présence à Toronto a été le centre d’intérêt de la couverture médiatique de la semaine. Lors d'un festival qui cultive les files d'attente en soit, l'un pour un question-réponse avec l'acteur Ed Norton a commencé la nuit précédente. À cette occasion, sa voix grave répondant à celle aigu de Norton, il avait surtout parlé Darkness on the Edge of Town, son disque "colère", qu'il explique principalement par son désir d'écrire sur la génération de ses parents et de leur lutte pour faire correspondre à la promesse des Etats-Unis avec leur réalité - "honorer mes parents et leur histoire et les gens que je connaissais: personne n'écrivait rien là dessus" - ni pour réfléchir à l'ère post-Vietnam et la perte d'innocence de son pays. Artistiquement, il a été influencé par l'attitude du mouvement punk, par des films tels que Mean Streets et par ses voyages à travers les États-Unis, qui l'ont sorti du New Jersey pour la première fois pour l'envoyer dans le paysage épique qu'on peut entendre sur l'album. Mais surtout, il s'agissait de récupérer quelque chose de lui-même, après la gloire. "J'ai eu mon premier goût du succès, et je pense que vous vous rendez compte qu'il est possible que votre identité soit cooptée", dit-il. "Lorsque vous avez un peu de succès, vous avez une variété de choix. J'ai regardé quelques-unes des cartes que les gens avant moi avaient dessinées. 'Ici, il y a des dragons!' Et la terre leur semblait plate, et pourtant ils tombèrent dans le vide. Et c'était quelque chose que je préfèrais ne pas faire. Et une partie de cela me renvoyait une conscience de moi-même." Il est devenu "un mutant dans votre quartier". "J'ai décidé que la clé était de maintenir un sentiment de moi-même, étant entendu qu'une partie de moi-même avait été mutée... Il y avait une poussée de l'instinct de conservation plus que toute autre chose." Dans le restaurant, le point où il a construit un cercle intérieur est palpable et il l'a renforcé au fil des décennies: Landau et Barbara Carret sa co-manager, la même maison de disques, le noyau dur du E Street Band est resté inchangé dans son ensemble depuis ses débuts. Il parle de cette unité, la façon dont le cinéaste Thom Zimny s'est intégré dans une équipe qui "va au delà de l'engagement" et un groupe qui doit le rester, afin de remplir sa mission déclarée. Dans une Amérique politiquement clivée, il est maintenant aussi important - sans doute plus - en dehors de son pays d'origine. Même parmi les convaincus, la réaction des États-Unis ne correspond pas exactement à celle qu'il reçoit en Scandinavie, en Italie, en Espagne et en Irlande. Landau l'avait dit plus tôt, Scialfa l'a rappelé au cours du déjeuner, et Springsteen en rajoute. "Ils apportent une telle passion avec eux, et vous vous nourrisser de cela," dit-il, "mais sans le vide qui vient habituellement de louer du public d'un pays ou d'un autre." Il ya sept ans, il a donné un spectacle unique au RDS. Au cours de 2008 et 2009, il y a joué cinq fois. Je me demande si cette relation a été cimentée lors de la tournée Seeger Sessions en 2006, quand la musique folk lourde a été appréciée ici à un niveau inimaginable ailleurs. "Non," dit-il, "c'était sur Devils and Dust. Je suis venu et a joué au The Point, et j'ai pensé que j'aimerais juste faire 10 fois ces spectacles. Il y avait une intensité puissante lors de ce spectacle." Il était en effet, bien aidé par le fait qu'il pleuvait si fort que la batterie sur le toit donnait un duo atmosphérique à ce qui était une performance solo. L'intensité du public est, cependant, une réponse à son propre engagement sur la scène. Il a tourné sans relâche au cours des dernières années - 11 shows dans la seule Irlande depuis 2005 - et la dernière fois, il a joué près de trois heures avec une brillance à faire trembler sans même prétexter un faux départ pour un rappel. "Il faut vouloir le faire," dit-il. "En outre, vous devez le montrer, pas le dire. C'est pourquoi ça s'appelle du "show" business, et non du "tell" business. Il parle de Sting qui lui avait dit une fois "tu travailles trop dur", puis plus tard d'ajouter: "oh, je comprends, c'est la seule façon de savoir comment le faire." La démarche de Springsteen doit être suivie par le groupe , et il n'autorisera aucun fléchissement. "Je placerai chacun de nos shows actuels au même niveau que ceux d'il y a 30 ans" dit-il. "Je veux que ce soit de telle façon que si ton frère vient nous voir là maintenant, il ne nous aura jamais vu jouer mieux. Si ton père vient, il ne nous aura jamais vu jouer mieux. Si vous êtes grand-père vient, il ne nous aura jamais vu jouer mieux." Depuis le début de la décennie, il est devenu fasciné par son propre passé et tient à le référencer. "Je suis devenu intéressé par l'histoire de du groupe, à le réunir", dit-il. "Pendant longtemps j'ai été mal à l'aise avec les tournages, mais il y a 10 ans, nous avons décidé de tout filmer. Et il s'agit de réunir des choses pour tous ceux qui sont nouveaux pour nous, qui sont venus à nos concerts et qui commencent à nous écouter, mais qui n'étaient même pas nés quand Darkness est sorti." Il y a deux ans Born to Run a reçu le même traitement avec un coffret, mais ce qui rend Springsteen si vivant est qu'il n'est pas tourné vers le passé par la nécessité de rappeler au monde de sa pertinence. Avec son producteur Brendan O'Brien, il a trouvé une main ferme sur les albums récents, mais le noyau a bien été la créativité en état de grâce de Springsteen. Son plus récent album Working on a Dream, était en quelque sorte un soupir de contentement après les albums précédents qui étaient politiques (Magic, les sessions Seeger), intime (Devils and Dust) ou couvrant à la fois la douleur personnelle et publique et de la résilience (The Rising). Et bien, même Working On A Dream est une exhalation de soulagement, après l'élection de Barack Obama. Sa musique, dit-il, a toujours été la recherche de ce qu'il appelle l' "essentiel", cet élément qui arrive à la base de l'expérience de chacun, "cette chose essentielle qui compte pour moi, ce qui compte pour lui, ce qui compte pour vous" . Il est resté fidèle à une phrase de Martin Scorsese pour avoir un public "attentif aux mêmes obsessions que vous". Darkness a été le début de ce qu'il appelle le "long récit" de ses compositions, une histoire qu'il se mit à raconter avec lui et qu'il s'est engagé à poursuivre à travers chaque chose depuis. Lors de la soirée précédente, il avait dit à Ed Norton qu'il a toujours compris cette nécessité. "J'ai dit il y a d'autres gars qui jouent de la guitare bien, il y a d'autres gars qui se mettent vraiment bien en avant, il y a d'autres groupes de rock ailleurs. Mais l'écriture et l'imagination d'un monde, c'est une chose particulière, vous savez. C'est une empreinte digitale unique. Tous les cinéastes que nous aimons, tous les écrivains que nous aimons, tous les auteurs-compositeurs que nous aimons, ils ont mis leur empreinte sur votre imagination, dans votre cœur. Et sur votre âme. C'est quelque chose qui m'a touché, et j'ai pensé, eh bien, c'est ce que je voulais faire." Cela signifie que ses thèmes étaient non seulement politiques ou sociétals, mais très personnels. Il écrit, après tout, sur le vieillissement d'une manière courageuse que peu d'autres artistes ont eu. Il doit y avoir un engagement à cela, dit-il. Il doit être sans faille, ne doit pas avoir peur de dire que les gens changent, prennent de l'âge, et que vous devez faire avec. "Ecrivez là dessus, dit-il. «n'ayez pas peur de ça." Lors de l'enregistrement de Darkness live, il a exigé que les décennies soient montrées brutes. Il a trouvé cette idée via une source improbable. "J'ai vu ce film de Jean-Claude Van Damme. Je ne sais pas si vous l'avez vu: il est appelé JCVD, et il se joue en lui et est pris dans un braquage de banque. Mais il est filmé de cette manière délavées, très gris, et il montre vraiment son âge. Et j'ai dit à Thom, c'est ce que je veux pour cet enregistrement." Springsteen a passé les 61 ans jeudi. Il est bronzé, frais, et même les patte d'oie sont tendues. Ses cheveux sont suffisamment sombres que vous vous demandez s'ils sont teints, mais on trouve des saupoudrages de gris autour de ses oreilles. Il a un enthousiasme qui semble émerger par le biais de ses 27 ans, une mèche de jeunesse qui contine de brûler. Il parait évident que, au cours de ces deux jours, Springsteen a retourné plus d'une fois à la notion de survie, à une Darkness enregitrée avec une intensité née de l'idée que cela aurait pu être le dernier album. Freinée par la querelle juridique avec son manager, Springsteen devait survivre par les concerts et par la réputation de Born to Run. Cet album avait fait de lui une star mondiale et a été la chose qui l'a mis la même semaine sur la couverture de Time et Newsweek en 1975. Dans un sens, il avait aussi le pouvoir de le tuer. De cette perspective, Darkness fait partie intégrante du déroulement de sa carrière, mais de son propre point de vue, à l'époque, il aurait pu en être la fin. Il exprime une profonde fierté du résultat, de comment ça sonnait alors, de comment ça sonne maintenant. Mais il est aussi clair que son excitation est ouverte à partir d'une vive satisfaction qui ne consiste pas seulement de revoir un album, une séance, quelques séquences vidéos anciennes, qu'il ne s'agit pas seulement d'une fête avec nostalgie, mais qu'il s'agit de revisiter un détour sur la route avec la satisfaction de savoir que le jeune qu'il était a choisi la bonne voie. Le déjeuner se termine. Springsteen n'a mangé son repas qu'à moitié, accompagné d'un verre de jus d'orange en grande partie intacte. On doit le pousser pour partir prendre son vol. Dix minutes plus tard, une photo est envoyée sur Twitter par quelqu'un qui vit à coté du restaurant. Springsteen, en chemise à carreaux, jeans et lunettes de soleil, avec un grand sourire, assis sur une moto dans la rue, posant avec un fan. Ca fait la journée de quelqu'un. Vous auriez du mal à dire de qui. merci à philippe35! |

In Toronto for the premiere of a documentary about the career-defining album that could so easily have been his last, a youthful 61-year-old Bruce Springsteen talks about retracing his steps to a creative fork in the road

In Toronto for the premiere of a documentary about the career-defining album that could so easily have been his last, a youthful 61-year-old Bruce Springsteen talks about retracing his steps to a creative fork in the road