But will the world be ready for Nils Lofgren?

15-11-1975 Musical Express par Nick Kent"No longer is the rock impulse revolutionary — i.e., the transformation of one's self and society —-but conservative: to carry on the rock tradition."

It's all a bit comic at first, but you don't laugh 'cos by this time you've zeroed right in on his face which really is quite striking—handsome even, in its tough neanderthal punkishness complete with a heavy 12 o'clock shadow that Jack Elam would've been proud of. The scene of the crime here happens to be the main hall of the Croydon "Greyhound" Entertainments Centre — one of those nouveau multi-storey constructions that have sprung up in a determined attempt to cater for the predominantly rootless youth of the nether suburbs. It's already dark outside and to celebrate the fact a handful of the town's inhabitants straggle around the door, looking suitably bedraggled and frozen. Inside it isn't much warmer and Lofgren is nursing his fingers from the chill manifesting itself in the hall. Mischief, it soon becomes evident, is the last thing on his mind. A sound-check is attempting to be conducted, though only Lofgren and his younger brother Tom are in evidence, axes in hand, on the stage itself while the rest of the Lofgren entourage — manager, rhythm section and roadies — amuse themselves with good innocuous all American fun in the shape of a frisbee. Everyone is too preoccupied staring mindlessly at this yellow plastic saucer careering from corner to corner to pay too much attention to Nils' and baby brother up there on the rostrum which, for once, is strange because Lofgren Snr. with his small limbs, big guitar and mild manneredly earnest Man With A Mission persona is the absolute centre-pin of the whole operation; the focal point around which all these comparative "nebisch" counter-parts jell themselves. NILS LOFGREN is principally all about "connection," see. On all levels. Connection with a band which while musically more than competent is the visual apotheosis of everything innocuously nada as regards the "faceless musician." Right on up to the big "mission" itself which is Connection with that most noble of rock 'n' roll pursuits: the continuation of the tradition laid down by the "heavies" — the buccaneering guitar-fetish heroes and villains . . . Eddie Cochran, Hendrix, Keith Richard, Pete Townsend. Johnny "Guitar" Watson. And now, maybe Nils Lofgren. As he stands on the stage, alone now, drifting off on some distant guitar spindrift, you suddenly realize you've forgotten completely about Lofgren's size and the absurd Marx Bros, threads, and when he tilts his head up at that angle he looks just like another rather less heralded but still bonafide upholder of this fine tradition, the MC5's Wayne Kramer. Only Lofgren's now playing the kid-brother to Kramer's gun fighter who's suddenly sharp enough to outdraw even his next-of-kin. Which in turn, makes you want to go right back and delete that "maybe." NILS LOFGREN. That's pure Swedish — the kind of name Max Von Sydow would be landed with if ever he and Liv Ullman were to be cast in an M.G.M. smorgasbord epic whimsically documenting the travails of some ersatz Scandinavian equivalent of the Pilgrim- Fathers wending their way across to the Promised Land. But that's only half the story. Lofgren's father was another Nils Lofgren — of Swedish extraction natch, who came to America and ended up in wedlock to a nice Italian girl. Pure Sicilian, in fact. That's where Nils the younger gets those Italianate features. Not to mention his talent for accordion playing. The whole family spent some years in the Italian quarter of downtown Chicago where it's tradition for the first-born to be initiated into the craft of playing the instrument. Great for a solo spot at weddings. Lofgren was ever taking classical lessons before he'd made his teens. It was Maryland, though — Maryland in Washington, D.C. — where the child prodigy first picked up on the rhythms of rock 'n' roll. He started on guitar, aged 15, first learning chords from Beatles records, then' lead breaks from the Animals. At 16 he witnessed, at Maryland's Ambassador Theatre. Hendrix and that iced it. "It was his first-ever tour of the States and he was so full of life, y'know ... so much energy. And it was ... well, for a start, a three-piece band was entirely unheard of then and everyone was thinking . . . y'know 'What is all this?' Then he came on and I mean, he just blew everybody apart." Lofgren may be semi-renowned for his idolization of Keith Richard but Hendrix is easily the mainman where this boy is concerned. Photos of "the man" festoon the inside of his guitar case as well as lay prone on the table in his hotel room next to a Bruce Lee memorial booklet (Lofgren is well enamored with these high energy types). Oh, and contrary to what you might read elsewhere in this issue the Lofgren stage stance owes far more to the Hendrix school of gum-chewing nonchalance than to K. Richard's patented smacked-back elegance trip. Anyway, after the Hendrix initiation came the "first bands". Names like the Waifs, the Grass, the Crystal Mesh, Sassafras Dynasty more than adequately define the stages being passed through. Finally there was Grin — "I heard someone say it and I thought... y'know it'd just be a good name." Made up of local D.C. hotshots (just like the new band, in fact) Grin could boast itself as the king-pin combo in Maryland, D.C., with Lofgren at centre stage already primed for "connection-bridging” with his sprightly palling up with famous names. The first was Roy Buchanan, highly regarded virtuoso guitarist, though a rather hang-dog figure due to heavy domestic commitments i.e. Southern belle wife and "five or six children". Buchanan worked the bars in Maryland by night and held down a day-time job as a barber — "I used to go down to the barbership and hang our with him." Buchanan was almost going to become a full-fledging Grinner at one point but that fell through. The guitar-player though did aid Lofgren's progress when he invited the latter to jam on an educational T.V. spot he secured. They chose "Shotgun" for the duel and Lofgren's nimble fingers and more punchy attitude ran smoke rings around Buchanan's methodical expertise. Buchanan even broke a string at one point which didn't help matters and Lofgren came up trumps. THE OTHER connection was made with Neil Young — at that point not anything approaching the enigmatic figure he is now — and Danny Whitten's Crazy Horse. Lofgren more or less joined Crazy Horse for their first, great album. Those were great times Lofgren reminisces, with Jack Nieizche's erratic genius meshing with Whitten pained quavery voice (which he'd perfected. Nils claims, before Young used it as his trade mark). Unfortunately, Whitten started to degenerate into junkie dom almost immediately followng. the album's completion consequently splintering the band. Nietzche leaving in disgust and Lofgren stepping back to view the Whitten miasma with frustration. "But what can you do? You're on the road and you're spending all your time and energy keeping yourself together. You can't afford to get too involved with another guy's problems in that situation. It's a harsh reality.'' Lofgren did in fact move in with Whitten when the latter was irreconcilably "gone" and all attempts at help were rendered futile and obsolete. The period, short as it was is not one festooned with particularly pleasant memories for Lofgren. "When they phoned me up with the news that he died, sure I was bummed out but what could we all do?" Neil Young's reaction was rather more personalized but we'll get to that in a while. Young, as is now common fact, took the teenage Lofgren under his wing and splashed his talents liberally over "After The Goldrush". Meanwhile, there was Grin who were signed by Clive Davis to Spindizzy, a Columbia subsidiary label, from whence were three albums — the first exhilarating promising, the second a bona-fide rock 'n' roll classic. The third — well, the third started telling the full story — Grin were a classic example of the band who never had the commercial breaks due to finding themselves trapped in the treadmill — a dead end situation revolving around ceaseless tours, third-billing to the likes of Edgar Winter, J. Geils and Black Oak Arkansas which placed a giant strangle hold on creativity as regards song- writing and recording in general. The third and fourth Grin albums were painfully disappointing for just those reasons. In an attempt to shape up to the situation, Lofgren, never one to hold back onstage though his performances were more tied to quasi-juvenile intense energy pile-drives, decided to compete with the flashier front-liners, dragging in a trampoline on which he'd perform "flips" while playing a guitar solo. "At all those gigs, it was the same. Total apathy up until the time of the 'flip' at which point they'd all go crazy and demand an encore." Little wonder then, that in the midst of all the frustration was slowly driving the Grin consortium to call a stalemate to their battle against deaf ears, lean breaks and energy-strafing road routine, Lofgren should up and moonlight off with old buddy Neil Young for a tour where personal pressures to "deliver" were minimal, crowds were receptive and the itinerary took in several European countries that the boy wonder had previously only ever-dreamt of visiting. Nils, by his own admission, claims to initially have taken the gig without really understanding Young's motives for the venture. The tour, you see, was the now infamous "Tonight's The Night" gambit of 1973 — a bizarre event anyway you look at it — half off-the-wall stumblebum booze orientated, the other half a kind of equally off- the-wall personal mission on Young's part to tune in on the strange death vibe he personally felt resonating from the departed spirits of O.D.'d junkie malcontents Whitten and Bruce Berry. Young's whole intense commitment to the Whitten-Berry deaths to this day remains as bizarre as it is grimly inspired (face up, "Tonight's The Night" is the most profoundly uncompromising rock documentary of the '70s wastelands since "Exile On Main Street") and therefore tended to bemuse even the musicians involved. Lofgren, for example, expecting perhaps a looser, more straight-ahead rock 'n' roll approach to the alliance, even brought his trampoline along with him. "I found out pretty quickly that it wouldn't be used (laughs). "But then again, I was easy, see. I knew it wouldn't last that long. Initially I'd done it as a favour to Neil. I had just no idea what was on his mind at the outset. I mean, I loved Danny Whitten, sure, but Neil's reaction to all that was something else again. I certainly wasn't into trying to raise up any dead spirits." To add to the confusion. Young's manager Elliot Roberts took it upon himself to try and extricate his golden boy away from this brazenly uncommercial left-field bent of his, and get him back sitting pretty again with money-spinnin' CSN&Y — at least for the duration of a highly lucrative reunion tour. "Let's just say that all that was in very bad taste. I mean, he (Roberts) would always pick the times to confront Neil and badrap the whole trip when the rest of the band were around and that was hardly of benefit to the collective morale of the musicians involved. As the tour went on, I just felt a stronger and stronger commitment to simply finishing it." Returning immediately to D.C. and Grin, Lofgren and the band, by now freshly signed with A&M (the fourth Grin album entitled "Gone Crazy" their first and last as a collective — for the new label was never released here. In retrospect, it's easily Lofgren's least inspired collection of songs though such ruthless anonymity scarcely befits any talent as dazzling as Lofgren's can be) set out on the road in January of '74. They made it up as far as June of that year and simply called it quits. "I look back in retrospect at Grin and I think, boy, we had great potential but we just didn't fulfill that potential. That's all. Our albums started going down in quality simply because we found ourselves locked into these gruelling road schedules which drew every last drop of energy from all of us. On the one hand, for the first Grin album I had all those songs written out two years before we ever went into the studio. By the third or fourth, I was faced with recording sessions set at random and scarcely any time to really sit down and satisfactorily work out whatever ideas I'd amassed over that period. It eventually ended up maybe a little too confusing — and frustrating I guess, to warrant a whole lot of attention." If Lofgren at times seems puzzling in the resigned, almost indifferent way he so often views his Grin days, it's maybe to be put down to a strange perfectionist streak he constantly displays in regard to his duties as a musician. He more or less dismissed the superlative second Grin album totally, for example, simply because the vocal tracks throughout just don't measure up to his present standards, so he claims. A "Best of Grin" compilation would be "nice," he admits, but there's this throwaway quality to the way he will dutifully add "Yeah, if there should ever come a time when such a project might just be in demand" that you wonder if he really cares either way — even if he and his manager have a title — "Grin's Last Laugh" — already set. O.K., SO Nils Lofgren is an artist and he don't look back, but he still can't lay claim to having the facilities to possess everything he needs. In order to "connect" you've got to have, recipients, dig and that doesn't just mean rock writers spreading the superlatives — that's only one fraction of the drain reaction. Which brings us right back to the present and the Croydon Greyhound, I guess. Hardly an auspicious venue, of course. I mean, Bruce Springsteen won't be gigging here and for all the ballyhoo, I can't honestly imagine him being any better live than Nils. Fact is. I can't imagine anyone topping Lofgren this night at the Greyhound. The thin red spotlight zooms in first of all, hits him dead in the face and Lofgren's up and crooning this dumb, tender little song from the first Grin album very slow and passionate. Then he stiffens up and slams right into his monster rock hit single of the year that-never-was called "Back It. Up" and I'm smiling to myself first because here's this punchy little renegade urchin pulling off some of Hendrix's best moves and making them all his own over a riff that Keigh Richard would probably have given his (new) teeth to pick up on first and second because flexed behind those tough boy- girl situation lyrics lays the whole basic Nils Lofgren credo from A to Z — "Back it up, baby, love ain't enough/I need devotion to back it up." Just like earlier that afternoon when he was talking about the Stones and how he'd been all psyched up to join them after he'd called Keith up from L.A. back last March sometime and heard that the gig was still open. "I mean, I was ready, man. I just wanted to be given, say, ten songs to learn straight off and work out with Keith. It could've been good too. You know, I'd never step out into that kind of heavy territory unless I knew I could back it up. And later when I asked him whether he saw himself as one of the last in that noble tradition of rock 'n' roll buccaneers, or one of the first in a whole new baby ga… ¦ breed. Lofgren mused for a moment and then replied that it was just part of a continuing process really. New kids turn up when it starts to sag. Look at Springsteen. "The basic common bond is that all the greats could 'put out', y'know, and they were for real. I mean, you just can't fool anybody. Keith Richard ain't fooling anybody, man. And neither am I." Yet all the while I'm worried for Lofgren. Worried because on the one hand he's just so damn good and yet while the Springsteens and Patti Smiths — both space cadets from the same badass peer group — are getting all the Newsweek and Rolling Stone covers and having it all poured out for them. Nils is still basically scuffling for the Big Connection. But, then again, I suppose one could make a far heavier comment on the apparent fact that rock 'n' roll's future bloodshots will more than likely be administered by the daunting combination of a dykey beat poetess, and a would-be Jewish- American princeling. With the Swedish midget on outsider's odds, of course. |

Mais le monde sera-t-il prêt pour Nils Lofgren?

"Le courant rock n’est plus révolutionnaire - c.-à-d., la transformation de l’individu et de la société - - mais conservateur : pour perpétuer la tradition du rock."

C’est tout à fait cocasse au début, mais vous ne vous marrez pas parce que dès que vous avez pointé votre regard droit dans son visage qui vraiment est assez frappant - beau même, dans sa dure pâleur de Neandertal que rehausse une écrasante ombre de midi dont Jack Elam aurait été fier. La scène du crime ici s'avère justement être le hall principal du Croydon "Greyhound" Entertainments Centre - une de ces constructions art moderne à plusieurs étages sortis de terre dans une tentative résolue d’intégrer la jeunesse déracinée des banlieues difficiles qui prédomine. Il fait déjà noir dehors et pour célébrer l’occasion une poignée des habitants de la ville s’agglutine auprès de la porte, l’air tout à fait débraillés et frigorifiés. À l'intérieur il ne fait pas plus chaud et Lofgren protège ses doigts du froid qui règne dans le hall. La pitrerie, cela devient vite évident, est la dernière chose qu’il a en tête. Une balance est en cours, bien que seuls Lofgren et son jeune frère Tom soient visibles, guitares à la main, sur la scène même tandis que le reste de l'entourage de Lofgren - manager, section rythmique et roadies - s'occupent avec un jeu bon enfant typiquement américain sous forme d’un frisbee. Chacun est trop préoccupé à regarder machinalement cette soucoupe en plastique jaune qui file d’un coin à l’autre pour vraiment prêter attention à Nils et son petit frère là haut sur l’estrade, ce qui, pour une fois, est étrange parce que Lofgren Senior, avec ses petits membres, sa grande guitare et le personnage d’Homme Porteur d’une Mission légèrement maniéré est le pivot absolu de toute l'opération ; le point focal autour duquel tous ces alter-ego "empotés" en comparaison, prennent de la consistance NILS LOFGREN se soucie principalement du "lien", Je m’explique. À tous les niveaux. Lien avec un groupe qui, tandis que plus que bon musicalement est l'apothéose visuelle de tout ce qui est innocemment nada aux côté du "musicien sans visage." En prise directe avec la grande "mission" elle-même qui est le Lien avec la plus noble des quêtes rock : la continuité de la tradition établie par les "Grands" - les guitare héros fétiches boucaniers et canailles… Eddie Cochran, Hendrix, Keith Richard, Peter Townsend. Johnny "Guitar" Watson. Et maintenant, peut-être Nils Lofgren. Pendant qu'il se tient sur scène, seul à présent, la tête ailleurs sur un vague air de guitare de Spindrift, vous réalisez soudainement que vous avez complètement oublié la taille de Lofgren et les fringues absurdes à la Marx Brothers et quand il incline sa tête vers le haut, vu sous cet angle, il ressemble simplement à un nouveau défenseur plutôt moins proclamé mais sincère de cette belle tradition, le Wayne Kramer de MC5. Seulement Lofgren est maintenant en train de jouer au frangin du flingueur de Kramer qui est soudain assez pointu pour surpasser même son proche parent. Ce qui à son tour, vous incite à vouloir revenir en arrière et supprimer ce "peut-être." NILS LOFGREN. Ce Suédois pur jus - le genre de nom avec lequel Max Von Sydow aurait pu se retrouver si jamais lui et Liv Ullman avaient dû tourner dans un méli mélo à grand spectacle de la M.G.M. décrivant de manière saugrenue le dur labeur de quelque ersatz Scandinave comparable aux Pèlerins Fondateurs se frayant un chemin à travers la terre promise. Mais c'est seulement une partie de l'histoire. Le père de Lofgren était un autre Nils Lofgren – d’extraction suédoise naturellement, qui est allé en Amérique et s’est retrouvé marié à une jolie fille italienne. Sicilienne pure, en fait. C'est de là que Nils le jeune tient ces côtés Italiens. Sans compter son talent pour jouer de l'accordéon. La famille entière a passé quelques années dans le quartier italien du centre de Chicago où c'est la tradition que l’ainé soit initié au métier de musicien. Idéal pour se faire un petit billet aux mariages. Lofgren n’a jamais pris que des leçons de classique avant l'adolescence. C'était le Maryland, cependant - le Maryland à Washington, D.C - où l’enfant prodige s’est mis pour la première fois aux rythmes rock. Il a commencé la guitare, à 15 ans, apprenant au début avec les disques des Beatles, ce qui l’a ensuite amené aux Animals. A 16 ans il découvre Hendrix à l'Ambassadeur Theatre du Maryland et ça le tue. "C'était sa première tournée aux States et il était tellement plein de vie, tu sais… tant d’énergie. Et c'était… bon, pour un début, un groupe de trois éléments totalement inconnu et chacun pensait… tu sais "c’est quoi ce truc?" Alors il est entré sur scène et je veux dire, il a juste mis tout le monde sur le cul" Lofgren est peut être assez connu pour idolâtrer Keith Richard mais Hendrix est de loin le le préféré du garçon. Des photos "de l'homme" tapissent l'intérieur de la caisse de sa guitare tout comme d’autre sont étalées sur la table dans sa chambre d'hôtel au côté d'un livret souvenir de Bruce Lee (Lofgren est dingue de ces types débordants d’énergie). Ah, et contrairement ce que vous pourriez lire ailleurs dans cette publication la posture de Lofgren sur scène doit bien plus à l'école de nonchalance du gars qui mâche du chewing-gum à la Hendrix qu’à l’élégant et breveté mouvementent retourné de K. Richard. Quoi qu'il en soit, après l’initiation avec Hendrix sont venus les "premier groupes". Les noms comme The Waifs, The Grass, The Crystal Mesh, Sassafras Dynasty définissent plus que justement les scènes traversées. Enfin il y eu Grin - "j'ai entendu quelqu'un le prononcer et j’ai pensé… tu sais ça serait juste un nom pas mal." Composé de quelques pointures locales du District de Columbia (juste comme le nouveau groupe, en fait) Grin pourrait s’enorgueillir d’être la cheville ouvrière des groupes du Maryland, D.C, avec Lofgren au centre de la scène déjà préparé pour "établir des liens" grâce à sa franche camaraderie avec des noms célèbres. Le premier fut Roy Buchanan, hautement considéré comme guitariste virtuose, malgré tout plutôt une image de chien battu en raison de ses fortes attaches conjugales c.-à-d. une belle épouse du sud et "cinq ou six enfants". Buchanan travaillait dans les bars du Maryland la nuit et avait un travail de jour comme coiffeur - "j'avais l'habitude d’aller au salon du barbier et de tuer le temps avec lui." Buchanan était sur le point de devenir un Grinner frais émoulu mais c’est parti de travers. Le guitariste a cependant contribué aux progrès de Lofgren quand il a invité ce dernier à faire le bœuf dans un spot de T.V éducatif qu’il avait décroché. Ils ont choisi "Shotgun" pour le duel et les doigts vifs et l'attitude plus dynamique de Lofgren lançait des anneaux de fumée autour de l'expertise méthodique de Buchanan. Buchanan a même cassé une corde à un moment qui n’arrangeait rien et Lofgren a sauvé la mise. L'AUTRE lien a été avec Neil Young - à cette époque rien de comparable à la figure énigmatique qu’il est maintenant - et le Crazy Horse de Danny Whitten. Lofgren rejoignit plus ou moins le Crazy Horse pour leur premier, grand album Ce furent de grands moments dont Lofgren se rappelle, avec le génie erratique de Jack Nieizche s’ajustant avec la voix douloureuse et tremblante de Whitten (qu'il avait perfectionnée. Nils le prétend, avant que Young ne l’utilise comme sa marque déposée). Malheureusement, Whitten commença à dégénérer, drogué au dom (ndtr: drogue psychédélique) pratiquement juste après la fin de l’album, brisant dès lors le groupe. Nietzche partant dégouté et Lofgren prenant du recul pour voir de nouveau le miasme de Whitten avec frustration. "Mais que pouvez vous faire ? Vous êtes sur la route et vous consacrez tout votre temps et énergie à vous garder uni. Dans cette situation vous ne pouvez pas vous permettre de devenir trop concerné par les problèmes d'un autre type. C'est une dure réalité." Lofgren s'est en fait installé avec Whitten quand ce dernier a été irrémédiablement "parti" et toutes les tentatives d'aide se sont avérées futiles et désuètes. La période, aussi courte soit-elle, n'est pas particulièrement émaillée de souvenirs agréables pour Lofgren. "Quand ils m'ont téléphoné pour m’annoncer la nouvelle de sa mort, c’est sûr j’ai pris un coup mais que pouvions nous faire ?" La réaction de Neil Young était un peu plus personnalisée mais nous y reviendrons plus loin. Young, c’est maintenant établi, prit le jeune Lofgren sous son aile et il a généreusement éclaboussé de ses talents "After The Goldrush". Au même moment, Grin était signé par Clive Davis à Spindizzy, un label d’une filiale de Columbia, d'où sortirent trois albums - le premier euphorisant de promesses, le second un véritable classique de rock. Le troisième - oui, le troisième commença à raconter toute l’histoire - Grin était l’exemple classique du groupe qui n'a jamais eu de passages à vide commerciaux car ils se sont retrouvés piégés par l’engrenage - une situation d’impasse qui gravite autour de tournées incessantes, la troisième partie de gars comme Edgar Winter, le J. Geils et Black Oak Arkansas ce qui a mis une chape géante sur la créativité en ce qui concerne l'écriture et l'enregistrement de chanson en général. Les troisièmes et quatrièmes albums de Grin furent terriblement décevants, précisément pour ces raisons. Dans une tentative de redresser la situation, Lofgren, qui n’est jamais du genre à se réfréner sur scène bien que ses performances étaient plutôt liées à une intense énergie débordante, quasi-juvénile, décida de faire concurrence à ceux du devant de la scène, plus voyants, se trainant dans un trampoline sur lequel il exécutait des sauts périlleux en jouant un solo de guitare. "À tous ces concerts, c'était pareil. Apathie totale jusqu'au moment du "saut pér" alors ils devenaient tous dingues et en redemandaient." Pas étonnant ensuite, qu’au beau milieu de tout cela la frustration conduisit lentement l’association Grin à mettre un terme à leur bataille contre les sourdes oreilles, les changements de régime et la routine de la route dévorante d’énergie, Lofgren devait se révéler et sortir de l’ombre avec son vieux pote Neil Young pour une tournée où les pressions personnelles de "résultat" étaient minimales, les foules étaient réceptives et l'itinéraire comprenait plusieurs pays européens que le jeune prodige n’avait même jamais rêvé de visiter avant. Nils, de son propre aveu, déclare avoir pris la route sans vraiment comprendre les motivations de Young pour l'entreprise. La tournée, vous voyez, était la maintenant tristement célèbre pantalonnade de 1973 "Tonight's The Night" - un épisode bizarre quelque soit l’angle sous lequel vous le regardez – Pour une part fait pour les abrutis alcolos déjantés, pour l'autre un genre de mission personnelle tout aussi déjantée de la part de Young pour se mettre en harmonie avec les étranges vibrations de mort causées par les mauvais esprits disparus des junkies morts d’overdose qu’étaient Whitten et Bruce Berry et qu’il ressentait personnellement. Tout l’intense engagement de Young dans les disparitions de Whitten-Berry reste à ce jour aussi surprenant qu'il est sinistrement inspiré (regardons les choses en face, "Tonight's The Night" est le documentaire sur les friches du rock des années 70 le plus résolument sans concession depuis "Exile on Main Street") et donc tendait à dérouter même les musiciens concernés. Lofgren, par exemple, s'attendant peut-être à une collaboration plus libre et plus en ligne avec le rock, avait même emporté son trampoline avec lui. "J'ai réalisé assez rapidement qu'il ne serait pas utilisé (rires). Mais finalement, ça m’était égal, tu vois. Je savais que ça ne durerait pas longtemps. Au début je l'avais fait comme un service pour Neil. Je n'avais vraiment juste aucune idée ce qu’il avait en tête au début. Je veux dire, j’adorais Danny Whitten, c’est sûr, mais la réaction de Neil à tout ça était tout autre encore une fois. Je n’avais certainement pas pour ambition de ressusciter des esprits morts." Pour ajouter à la confusion. Le manager de Young, Elliot Roberts prit sur lui d’essayer et de dégager son protégé de cette échappée éhontée et anti-commerciale qui lui collait au dos, et pratiquement aussitôt obtint de lui de revenir travailler avec le très lucratif CSN&Y (Crosby Still Nash & Young - ndtr) - au moins pour la durée d'une tournée de retrouvailles très juteuse. "Disons simplement que tout cela était de très mauvais goût. Je veux dire, Il (Roberts) trouvait toujours l’occasion de s’affronter avec Neil et de le dénigrer pendant tout le voyage quand le reste du groupe était à proximité et ça ne contribuait en rien au moral collectif des musiciens. Au fur et à mesure que la tournée avançait, je me suis de plus en plus promis de simplement en finir." Retournant immédiatement à D.C et à Grin, Lofgren et le groupe, alors fraîchement signé chez A&M (le quatrième album de Grin "Gone Crazy"," leur premier et dernier ensemble - sous le nouveau label ne fut jamais sorti. Rétrospectivement, c'est de loin la série de chansons de Lofgren la moins inspirée bien qu'un anonymat aussi strict ne sied à aucun talent aussi brillant Lofgren soit-il) partent en tournée en janvier 74. Ils ont tourné jusque juin de cette année là et simplement appelée "quits". "Je regarde Grin avec du recul et je pense, mec, nous avions un grand potentiel mais nous n’avons simplement pas exploité ce potentiel. C'est tout. Nos albums ont commencé à baisser en qualité simplement parce que nous nous sommes trouvés englués dans ces calendriers de tournée exténuants qui nous ont pris à tous chacune de nos dernières gouttes d'énergie. D'une part, parce que pour le premier album de Grin j'avais déjà toutes ces chansons écrites deux ans avant que nous soyons entrés pour la première fois en studio. Pour le troisième ou le quatrième, j'ai été confronté aux sessions d'enregistrement programmées au hasard et sans pratiquement aucun moment pour s’assoir vraiment et coucher de manière satisfaisante les quelques idées que j'avais amassées au cours de cette période. Cela s’est finalement terminé de manière trop déconcertante - et frustrante je pense, pour justifier assez d'intérêt." Si Lofgren semble parfois déconcertant dans la manière résignée, presque indifférente avec laquelle il regarde si souvent cette période de Grin, peut être que cela peut être mis sur le compte d’un curieux coté perfectionniste qu’il affiche constamment en raison de ses responsabilités de musicien. Par exemple, il a plus ou moins totalement mis sous silence le superbe deuxième album de Grin, simplement parce que dans l’ensemble les passages vocaux n’arrivent pas à la cheville de ses standards actuels, qu’il revendique. Un "Best of Grin" serait "sympa" admet-il, mais il y a ce caractère désinvolte au point qu'il s'ajoutera consciencieusement "ouais, si seulement un jour un tel projet puisse devenir une attente" que vous vous demandez si ça l’intéresse vraiment de toute façon - même si lui et son manager ont un petit - "Grin's Last Laugh" (le dernier rire de la grimace ndtr) - déjà en boîte. BIEN, AINSI Nils Lofgren est un artiste et il ne se retourne pas sur le passé, mais il ne peut toujours pas revendiquer d’avoir les talents de posséder tout ce dont il a besoin. Pour vous "mettre en lien" il vous faut des interlocuteurs, s’apprécier - et ça ne signifie pas seulement des auteurs rocks faisant des tartines de superlatifs – ce qui est seulement une fraction de l’épanchement. Ce qui nous ramène tout droit au présent et au Croydon Greyhound, je crois. On ne peut pas dire que ce soit un endroit accueillant, c’est sur. Je veux dire, Bruce Springsteen ne jouera pas ici et pour tout le battage, je ne peux pas vraiment imaginer qu’il soit meilleur que Nils. Le fait est. Je ne peux pas imaginer quelqu’un d’aussi bon que Lofgren cette nuit là au Greyhound. Tout d’abord le mince projecteur rouge grossit, le frappe en plein visage et Lofgren est debout chantonnant cette chanson légère et tendre du premier album de Grin, très lente et passionnée. Alors il se revivifie et se lance dans son hit single monstre de l’année qui-ne-l’a-jamais-été qui s’appelle "Back It Up" et je souris intérieurement au début parce que voici ce petit gamin rebelle et plein de vie extrayant certains des meilleures mouvements d’Hendrix et se les appropriant sur un riff pour lequel Keith Richard aurait probablement donné tout son mordant pour le reprendre primo et secundo parce que sous-tendu derrière ces textes durs de situation gars-fille repose l’essentiel du credo de Nils Lofgren, de A à Z - "Back it up, baby, love ain't enough/I need devotion to back it up." Tout comme plus tôt cet après-midi quand il parlait des Stones et de comment il avait été gonflé à bloc à l’idée de les rejoindre après que quelques fois en mars dernier il ait appelé Keith depuis L.A. et appris que le concert était toujours ouvert. "Je veux dire, j'étais prêt, mec. Je voulais juste qu’on me donne par exemple dix chansons à apprendre immédiatement et répéter avec Keith. Ca aurait pu être pas mal aussi. Vous savez, je ne me suis jamais aventuré dans ce genre de terrain miné à moins de savoir que je pouvais en revenir. Et plus tard quand je lui ai demandé s'il se voyait comme l’un des derniers boucaniers de cette noble tradition rock, ou l’un des premiers de toute une nouvelle espèce de bébés …(mot effacé ndtr) Lofgren réfléchit un instant puis il répondit que c’était vraiment juste un élément d'un processus continu. Les nouveaux jeunes apparaissent quand ça commence à faiblir. Regardez Springsteen. "Le lien commun fondamental est que tous les grands pourraient "s’éteindre", tu sais, et ils l’étaient pour de vrai. Je veux dire, c’est juste que tu ne peux duper personne. Keith Richard ne dupe personne, mec. Et moi non plus." Pourtant pendant tout ce temps je suis inquiet pour Lofgren. Je suis inquiet parce que d'une part il est juste sacrément bon tout autant que le sont les Springsteens et Patti Smiths – tous les deux cadets de l'espace issus de la même génération géniale - tous font les couvertures de Newsweek et de Rolling Stones et les font tous s’épancher sur eux. Nils en fait joue toujours des coudes pour créer le Grand Lien. Mais, à nouveau, je suppose qu'on pourrait formuler un commentaire bien plus péremptoire sur le fait apparent que les futurs têtes d’affiche du rock seront plus que probablement gouvernés par l’affolante combinaison d'une beat gouine et poétesse, et un pseudo prince de pacotille américano juif. Avec le petit Suédois avec la cote d’outsider, naturellement. Merci à Philippe! |

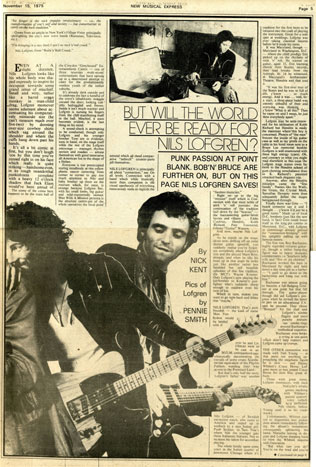

Even at a slight distance. Nils Lofgren looks like his whole body was shaped expressly to inspire its occupant towards some grand sense of mischief. Small and wiry, rather like a barrel organ monkey in man-child drag, Lofgren moreover seems adamant about accentuating his comparatively miniscule size (he can't measure much over five-two) by donning over-size cowboy shirts which sag around the shoulder and where the cuffs hang down past his hands.

Even at a slight distance. Nils Lofgren looks like his whole body was shaped expressly to inspire its occupant towards some grand sense of mischief. Small and wiry, rather like a barrel organ monkey in man-child drag, Lofgren moreover seems adamant about accentuating his comparatively miniscule size (he can't measure much over five-two) by donning over-size cowboy shirts which sag around the shoulder and where the cuffs hang down past his hands.