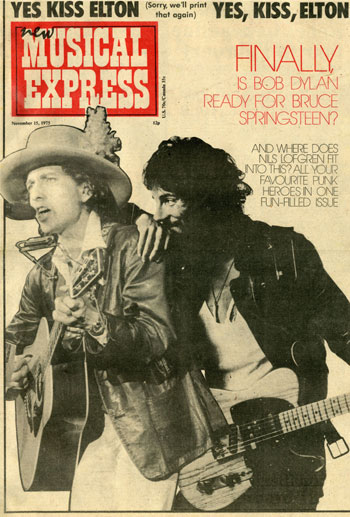

Is Bob Dylan ready for Bruce Springsteen?

15-11-1975 Musical Express par ?

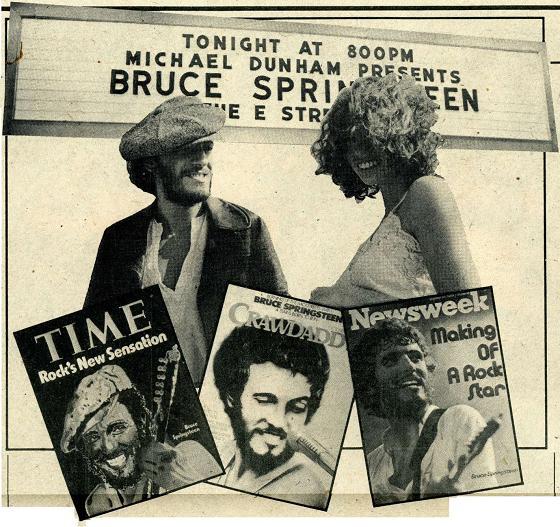

And it gets harder to decide what's best to believe because the people in from New York talk a lot louder than is natural and so do outsiders with a contrary understanding of the situation, coming on like a life depended on putting down the "I have seen mankind's future and it's a short, skinny guy in a brown leather jacket" theory. Bruce feels more than a little sick when he hears this kind of talk. His tendency, when it occurs, is to retire into a slow, agonized idiot-drawl, the relevance of which is not all that easily recognizable. But that's to his credit. Dylan, after all, never once said "Sure. I know the environment. The complexities of the human mind and things of that nature". And neither did James Dean or Brando when he was thin. It was only when Brando started whanging off in those kind of directions that his credibility was suddenly and irrevocably reduced. No. The only way to make a legitimate claim to American folk-hero status is to reject the candidacy as preposterous. Then clam up and spit à mysterious spit. And that's precisely what Bruce Springsteen from Freehold. N.J. is doing. Or you assume that's what he's doing, thing's for certain, though, and that's the fundamental lack of modesty within the Springsteen camp on the subject of the attributes and infinite potential of their boy. Jon Landau. The celebrated American rock critic who quit worrying over an intestinal disorder to co-produce Springsteen's "Born To Run" album says that in the "rock area" Springsteen's not only a "great artist" but also happens to be able to do "more things better than anyone else I've seen". Also he's the "best performer in the history of rock n’ roll", with the possible exception of Elvis P., whom he nominates mainly for "sentimental" reasons. Mike Appel offers scant contrast when he makes claims to being manager of "the greatest artist in the world today, that's all", a sentiment he punctuates by attacking the palm of his left hand with his right fist. Appel is a curiosity even among rock and roll managers. John Hammond, the Columbia talent scout who signed Springsteen, describes him as "offensive as any man I've ever met", a reference, no doubt, to Appel's boundless and sometimes absurd urges for conflict. Mostly it's the press who get to feel Appel's pointed end and this, it turns out, is no accident. "I like to do things with integrity", he notes, "and since the media is not set up for integrity but for their own ends, my idea of how things should be done and their idea of how things should be done, clash. So what happens is I'm the guy they focus all their hate on." Appel and Landau's extremities are matched by virtually everyone else within the Springsteen inner circle. Peter Philbin. Columbia's New York based international press officer, can talk up his client with a heat approaching delirium and at the recent Springsteen concerts at Hollywood's Roxy was not so much the impassioned go- between as one more nut on a chair howling his brains inside out. EVEN WITHIN HIS band, there's an awestruck, almost religious, regard for the man they call The Boss. Clarence Clemons, the 33-year old sax man, sees his meeting with Springsteen as being no less than divinely-wrought: "Bruce is the greatest person I've ever met," he says. "He's the strongest person I've ever met. When I first met him it was like in the Bible where this guy met this guy and he say 'lay down your thing and follow me' and that's exactly the way I felt, man. But I didn't. And I punish myself. And I guess God punished me 'cos I got in this car accident and I nearly got killed and shit. Anyway. He came back (from California where he'd been visiting his parents) and we got together and here we are." No less extraordinary has been the contribution of Time and Newsweek to the ballooning Springsteen legend and the apparent ease with which Appel was able to manipulate these two indefatigable giants. Time had previously run a piece on Springsteen in their April 1974 issue. Then a number of weeks ago Newsweek made approaches of their own and Time catching wind of the freshening scent came back for second helpings. The renewed interest had probably been spurred on by Springsteen's dates in August at New York's Bottom Line club, out of which came the most excessive Bruce-Is-Easily-The- Greatest Person-On-The Planet coverage to date.) This time, Appel explained, the rules were substantially altered. The game now was "you give me a cover. I give you an interview". "... and they have to dislike you for it," he says. "They say we're New Musical Express, we're Melody Maker, we're Newsweek, -we're Time magazine and who the hell are you to tell us it has to be a cover story. But I say to you 'I'm giving you the most coveted thing I can give you. I'm giving you an interview with Bruce Springsteen. There's nothing more I can give you." The indefatigable two returned and the net result was that double cover splash on October 27 (Appel's birthday). the first for an entertainer since Liza Minelli's Cabaret days. Both articles were strangely impartial considering the prominence they attached to their subject. Lots of biographical data input, a smattering of the dourest kind of rhapsodizing and — in Newsweek's case — a few microscopic insinuations that Springsteen might, after all, be the gravest kind of record business hypola which, by the laws of media cause and effect, would render themselves and Time the victims. A few years back the pair of them would have hung majestically to one side until the Springsteen legend knocked them down, then they'd have performed the gesture of the Cover Story. These days, even Time and Newsweek are fearful of missing out on the very next American sensation even if it means lining up at the wrong theatre before the box office opens. "It's crazy," says Springsteen. "It doesn't make too much sense and I don't attach too much distinction to being on the cover. It's a magazine. It goes all round the world but really ... you know."

"It doesn't have that much to do with what I'm doing," he says. "I don't think so. The main reason I went through with it ... you see one of the things I did want. I wanted Born To Run to be a hit single. Not for the bucks but because I really believed in the song a whole lot and I just wanted to hear it on the radio, you know. On AM. Across the country. For me that's where a song should be. "And they said, well if you get your picture on Time, or sumpin', programme directors may think twice before they drop it or throw it out. So the only physical reason I was on that thing was for that reason specifically, you know. Otherwise, man, I'll probably regret it, you know." Rolling Stone played an altogether cooler game. Still up in the air and blowing off over their Patty Hearst exclusives, their preference was to regard Springsteen as another of those East Coast phenomena, the kind that blows in and out with the frequency of the Atlantic tide. And Playboy ... Appel also tried to hustle a Playboy cover but was told that the Big Bunny would rather take it in the eye than set that kind of precedent. AND SO it was to the Roxy in Hollywood that the Springsteen entourage came October 16 to 19 to debunk the hype, perjury and associated theories, and it was with a deal of noise and small regard for the agreed subtleties that CBS applied themselves to the task. They began with a 50 per cent stake in the opening night house and bought in from there until your average man on the street needed air and ground troop support to get into the place. By way of consolation, a roster of Hollywood's brightest show-stoppers turned up to lend their support ... a line-up that by week's end included Jack Nicholson. G. Harrison, Jackson Browne, Neil Diamond. Jackie De Shannon (backstage introduction), Carole King (backstage introduction), Joni Mitchell (left early), Cher and Greg (twice), Tom Waits (hitched from his own gig 90 miles away), Dick Carpenter ("John, a Marguerita!") Wolfman Jack (?) and Warren Beatty.

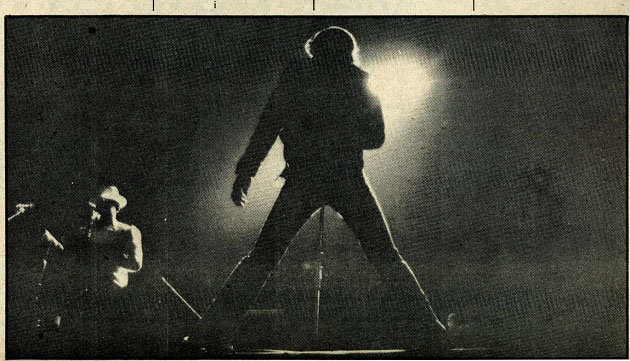

First night there was the usual pre-performance walking to and fro; the conspicuous nonchalance, Hollywood hugging, shouting across tables and explanations as to the root cause and nature of the Springsteen phenomena, and by the time Bruce actually walked out on stage everyone was so relieved at not having to exhibit epic boredom any more that the house lit up with a screaming and a wailing that must have scared him half to death. He heads straight for stage centre, which is dark, empty and almost eerie save for the screaming going on, leans his head and body against the mike stand and just to further irritate those Dylan comparisons whips out a harmonica for the opening of "Thunder Road". He's got on a beaten-up leather jacket, a pair of tight blue Levis. He's small, he's skinny and his harp playing's every bit as dumb as Dylan's.

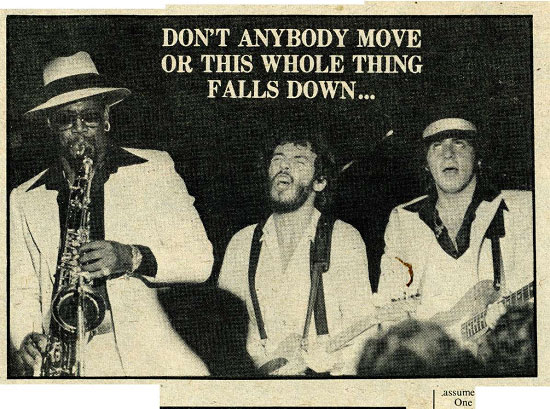

The Screen door slams A prelude to a number about a woeful girl waiting for her King Kong to come along and make sense out of her dreaming and Springsteen as the guy who says "what the hell, things might not be so perfect around here but let's jump in the old wagon anyway and take a ride along Thunder Road". Hey I know it's late we can make it if we run There's just a piano pumping away and Springsteen's knotty, out-of-tune voice ... and dead still. Head bowed. Brando, in "The Men", as his girl's telling him she'll love him forever even though his legs don't work anymore. Actually, it's all pretty embarrassing. And with folk through the house going "whoop, yeah ... you sure can make a guitar sing. Bruce", you feel kind of ominously out of sync. Then the band comes out for "Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out", also from "Born To Run", and the lights flash on and Springsteen starts whipping and winding up his body, attempting to lend the appearance of weight to what on record is a fairly inconsequential moment. Cluttered, dense lyrics. A melody and arrangement that are a patchwork of some of the more dubious R 'n' R mannerisms of the early sixties. "Spirit In The Night" is one of his few genuinely stirring melodies, even though it leans too heavily on Van Morrison. An early song from "Greetings From Asbury Park", a period when Springsteen was caught up with the flash of the exploding metaphor... gypsy angels, mission men and a preponderance of internal rhyme and lines that get left hanging. Crazy Janey. Wild Billy and a bunch more drive out to Greasy Lake "about a mile down on the dark side of route eighty-eight" where Janey's fingers wind up in the author's "cake". The love scene is played out in the dark with Springsteen lying prone across a line of tables that reach out to the stage. Girls rub his back as he sings "Me and Crazy Jane was making love in the dirt singing our birthday songs". Then the band and the spots light up, Springsteen jogs back to the stage and the house goes wild with delight (for Janey and her lover that night). For the opening of the old Manfred Mann number, "Pretty Flamingo", Springsteen delivers a rambling explanation- as-to-the-origins monologue that's half-heard, half-grunt and a pretty fine enactment of dumb bar house literacy. The kind of punchy drool that Dean gloried in. Everyone gets to feel mean in the presence of this kind of talk. More sordid still is the way he frames the opening to "E Street Shuffle". Here he tells the largely factual account of how he met up with sax man Clemons who'd been playing with a local Asbury Park R 'n' B band when a girlfriend told him he'd best go down to the Student Prince and look in on this kid Springsteen. The way Springsteen tells it, he and his guitarist Miami Steve were shuffling through the cold and foggy night when through the smoke they see a big man coming at them."They hide in a doorway and fall to their knees as the big man approaches. They're scared and they're cold and they're getting ready to run when Clarence holds out a hand, Springsteen reaches out to meet it. They touch. And sparks fly out on E Street. The magic of Springsteen is right here ... at the climax of this particular yam. On the word "sparks", the stage flashes red, Springsteen leaps to a standstill and the band lams in with the kind of precision entrance that occurs only when there's an operating consensus. From now on the show's alive, more refined ... a state of affairs that very nearly extends to the music itself. "Kitty's Back", "Jungleland" and "Rosalita" have that foggy West Side tilt to them and although neither is a miracle of construction there's enough ongoing momentum — and in the case of "Kitty's Back," a climactic instrumental segment — to eclipse the dubious areas. The band, in fact, is surprisingly adept at locating Springsteen's half-concealed intentions. Excellent solos are forthcoming in both "Rosalita" and "Kitty s Back"... especially from pianist Roy Bitten... and only organist Danny Federici. whose tendency is to grip the high end of the board a lot longer than is attractive, is suspect here. Just one encore tonight... a high drama mood piece with accordion and sometimes-whispered lyrics. "Sandy" is about Bruce, or someone a lot like Bruce, readying himself to quit the boardwalk life and it gives Springsteen the chance to open up on the reckless inhabitants of that whole scene. The clairvoyants, the bikers, waitresses, someone called Madame Marie, each of them shuffling back and forth from nothing to not much more. Lyrically it's one of his most interesting pieces, since it's one of the few moments he chooses to lay bare the disillusionment he patently feels for all the shucking from pintable to roadside diner to trash can which in most of his later works he's inadvertently glorifying. "Born To Run" he says, "was about New York. I was there for months. I had this girl with me and she'd just come in from Texas and she wanted to go home again and she was going nuts and we were in this room and it just went on and on. I would come home and she would say 'Are you done? Is it over? Are you finished?' And I said "No, it ain't over, it ain't over. I'd come home practically in tears." "And I was sort of into that whole thing of being nowhere. But knowing that there is something someplace. It's got to be like right there. It's got to be right somewhere."

BORN TO RUN had already been eight months in the making when Jon Landau (prev. exp. MC5's "Back In The USA" plus two Livingston Taylor albums) moved in on the job. With Landau around things continued to move at a deathly doze, although the further four and a half months taken to complete the package was, by contrast, an exhibition of fire and lightning. Landau attributes the delays to Springsteen's fetish for detail: "He'd spend hours", he says, "on one line. He'd say hang on guys, I wanna check a line' and four hours later he'd be sitting there trying to make the most minute changes in one verse." The pair had met April '74 in a Boston club called Charlie's where the Springsteen band was playing. In the club window was a blow-up of a review Landau had just written for the local Real Paper — an A- minus piece that dealt with Springsteen's "many imperfections" as well as his consider able potential for world domination. It was a cold night, Landau remembers, and he found Springsteen in the back garden in a t-shirt, jumping up and down as he read the review. Springsteen told him he'd read better but the piece was okay, and then Landau introduced himself. The show he saw that night he describes as "astounding" although no more than "a rough draft" of what takes place these days. The pair kept in touch and a month later Landau went into print with that high voltage review that Columbia subsequently spent 50.000 dollars promoting ... the "I have seen rock n roll's future and its name is Bruce Springsteen" job. Not that CBS didn't require an amount of cattle prodding before lining up behind the Springsteen/Landau combination. Factionalism within the company was rife ... due partly to the "flamboyance of Appel and the intractable nature of his client and also because Springsteen was a prodigy of "disgraced" chief executive Clive Davis. There were even reports of an alleged plot where the Springsteen myth would be hatched solely to irritate Bob Dylan, who'd recently left CBS for a two-record deal with David Geffen's Asylum Company. Appel himself goes more than half way to conceding that such a plan might well have existed. "When you're involved in big-time record company management'', he says, "There are power plays. There's how do you bring a Bob Dylan into line, how do you bring his lawyer into line.” "His lawyer comes in and asks for the world ... asks for retroactive royalties on Bob Dylan's albums. Asking outrageous sums of money. All kinds of deals. All kinds of big spending. And then when the negotiations fail, Clive Davis had left the record company and the whole world was looking at Columbia Records and everyone was taking pot shots at them. They were very nervous. Very uptight at this particular time, trying to prove themselves. Naturally they might have said, you know, in the heat of the moment, "screw Bob Dylan, we're going to take Bruce Springsteen and use him and show that guy just where its at'. However, that wasn't to be the case because it took us a long time to get our album together and "Blood On The Tracks" and all that had come out ahead of us. And they did manage to get Bob back." A suitably ironic climax to this particular episode was the request made through CBS by Time magazine for an interview with Bob Dylan on the subject of Bruce Springsteen. The request was rejected.

"They made the mistake," he says, "They came out with the big hype. I mean how can they expect people to swallow something like that? (CBS's early ads comparing him with Dylan). And it blows my mind how they can underestimate people so much. All the time, man, it's like ... trying to find some room, man. Gimme some damn room. Give me a break. I was trying to tell these guys at the record company, wait a se cond. you guys. Are you trying to kill me?" It was-like a suicide attempt on their part. It was like somebody didn't want to make no money. "I was in this big shadow, man, right from the start... and I'm just getting over this Dylan thing: Oh thank God that seems to be fading away' and I'm sitting home thinking thank God people seem to be letting that lie and phwooooeee I have seen... . No, it can't be. "So immediately I call up the company and I say get that quote out. And it was like, Landau's article. And it was really a nice piece and it meant a lot to me but it was like they took it all out of context and blew it up and who's gonna swallow that? Who's gonna believe that? It's going to piss people off, man. It pisses me off. When I read it I want to strangle the guy who put that thing in there. It's like you want to kill these guys for doin’ stuff like that. "They sneak it in on you. They sneak it in and they don't tell you nutin.' It's like shot gun murderer chops off eight arms." It's that kind of tactic, you know. It's that kind of tactic and they pull it for themselves and they pull it for me too... "It's a stupid thing. Ignore it, you know. Ignore the whole thing because it don't make any sense. So like I'm always ten points down cos’ not only have you got to play but you got to blow this bullshit out of people's minds first." It was so beautiful, I fell James Dean was back ... When I saw James Dean for the first time I fell on the floor. When I saw Bob Dylan for the first time I fell on the floor. When I saw Bruce Springsteen for the first time I fell on the floor: Jackie De Shannon over a cup of morning coffee. "Nah. it's like... if anything, you know. All I do, like, I write down my impressions of stuff, like, and what I see, you know. It's like... but if you're looking for something to look to... if you're into the band it's like... I don't know. I can't really see myself like that." Appel has a more adroit interpretation of the hype-versus- legitimacy dialectic and it goes like this: "I just say to myself "Listen fellows (of the press) Get out of that Bruce…”Why your vanities may have been up, your ego might have been up but let's stop the bullshit. The kid's really good. He's really different. If you've any kind-of talent you'll recognize him. If you don't you'll be run over. It's like a steamroller. We'll win in the end. You've got no chance against us. You've got no chance because we're right. We're good?" Appel used to write commercial jingles. He was also in the marine reserves and if he comes on a little like Ed Sullivan meets Joseph Goebbels that's roughly the way Springsteen sees it too. "It's like you can't lay an attitude on people. It's like bullshit. It's like a jive thing. It's a terrible thing. You can't come on like you're some big deal, you know. I ain't into coming on like that because it's a basic thing that's going on. It's a simple thing. It's a band, you know. It's a rock and roll band and you just sing and write songs. Appel got to meet Springsteen through an early mutual accomplice called Tinker. Tinker started out building drag racers in California, moved to Nassau where he helped launch astronauts into space and wound up manufacturing surfboards in New Jersey. Springsteen met him in a bar. He was 18 years old and Tinker said he could get him a job as a guitar player with Janis Joplin's band. "I ended up living with him in a surfboard factory for about a year and a half. It was dynamite up there." The first time Springsteen stepped outside the Jersey state line was with Tinker. Everyone in the band saved up a hundred dollars and drove out to California in a station wagon and a Chevy truck. Springsteen flipped from coast to coast during the next four years before realizing the best band he could ever have was waiting for him in NJ. In 1970 or '71 — he doesn't remember — Tinker took him to New York to meet with Appel and just like in a B-movie plot Appel is knocked out by the curly haired kid with the wooden guitar and within months has him eyeballing with the big record company talent scout. Springsteen at the time is reading Anthony Scaduto's book on Dylan and is fired up over the scene where Dylan launches himself into John Hammond's office, plays a couple of tunes and gets signed in a big hurry. So Springsteen and Appel try their hand and it works a second time. And that brings us through two low-impact albums followed by a regeneration of Columbia's corporate faith back to the Roxy in Hollywood where by week's end Springsteen is being exalted to a degree that puts you in mind of Appel's steamroller doctrine. By now even Walter Yetnikoff, president of the Columbia Records Group, is up on his chair, stirred, possibly, by the avalanche of dollars that is mounting in his imagination. The kids too — and by now it's the punter class — have taken on a demeanor that bears more than a passing resemblance to the early Beatle years, except these kids are older and so is Springsteen (26). But the years are no insulation against the Springsteen wall of faith as codified by Appel, Landau and Philbin and expressed, if haltingly by now, by Brucesteen himself. Time and Newsweek believed, and the punters believe because anything can be believed that is supported by the indomitable will of unyielding faith as manifest by the aforementioned. Springsteen could eat a camel whole, so long as he believed such a project wasn't outside his range, so long as the camel believed and the camel trader believed... or a king's new clothes situation where no- one notices the king's fat, naked legs until a kid says "Hey, where's his trousers" and all that faith drains away in a second and a half. Given that sooner or later someone's going to speak up, the deciding factor remains whether or not Springsteen actually has anything to cover his legs... that something being artistic substance and I’ll offer the opinion that Springsteen is indeed naked. That he's no more than a front man for another good rock and roll band, composer of R'n'B n B slanted, material that tips a little in advance of the mean average. The supposed profoundly cerebral inclinations are also misleading because Springsteen has neither the originality or the intentions — political or otherwise — of a Dylan which leaves him with a sackful of punk, loner mannerisms that he's already tiring of... a situation that probably caused the making of "Born To Run" to be such a vexed and anxious 12 1/2 months. Springsteen has a will and a strong dramatic style and the air of the all-American loner who the guys in the gang ask of 'where ya goin', Brucie?"and Springsteen grunts and goes off to the pier or to meet his girl whom he loves with a loyal and refined urgency as opposed to, say, Jagger, who could wake up anyplace and not remember how. And he exudes that dumb animal wisdom that made Brando and Dean such attractive propositions, - even though Springsteen tries to upset the image with literary pretentions. Appel, Landau and Philbin think they have to protect and talk up their man otherwise he dies, whereas Springsteen says tie needs protecting from Landau, Appel, Philbin and others of their mentality. So already the wall of faith is beginning to rupture and in six months Springsteen will be either musically wiped out, or more likely, another averagely regarded also-ran shouldering the resentment of punters and business types who by now see themselves as being suckered and duped. "I used to feel I always was in control," says Springsteen, 'but now I'm not so sure."

"Hey, you wanna see a rock n roll show?" (Bruce and girlfriend Karen). |

Bob Dylan est-il prêt pour Bruce Springsteen?

Et cela devient de plus en plus difficile de décider ce qu’il faut croire parce que les gens branchés de New York parlent beaucoup plus fort que la normale et les étrangers à la question qui ont une perception contraire font de même, se déchainant comme si la vie en dépendait en assénant la théorie « j'ai vu que le futur de l'humanité est c’est un type petit et maigre dans veste en cuir marron ». Bruce se sent plus qu’un peu mal quand il entend ce genre de discours. Sa tendance, quand cela se produit, est de s’en sortir en parlant d’une voix traînante d’angoissé facétieux, dont le rapport n'est pas du tout évident. Mais c'est tout à son mérite. Dylan, après tout, n’a-t’il pas dit un jour « Oui. Je connais le milieu. Les complexités de l'esprit humain et des choses de cette nature ». James Dean ou Brando quand il était mince n’ont pas agi différemment. C’est seulement quand Brando a commencé à taper dans ce genre de direction que sa crédibilité s’est soudainement et irrémédiablement réduite. Non. L’unique manière de faire une légitime revendication du statut de héros folk américain est de refuser sa candidature car ridicule. Puis de la fermer et de lâcher un mystérieux verbiage. Et c'est précisément ce que fait Bruce Springsteen de Freehold, New Jersey. Ou vous supposez que c’est ce qu'il fait, une chose est certaine en tout cas, c’est le manque fondamental de modestie au sein du camp de Springsteen à propos de ce qu’on lui prête et l’infini potentiel de leur poulain. Jon Landau. Le célèbre critique américain de rock qui, débarrassé de la crainte d’avoir un problème gastrique en coproduisant l’album de Springsteen « Born To Run» dit que dans la « mouvance rock » Springsteen n’est pas seulement un « grand artiste» mais s'avère également capable de pouvoir faire « plus de choses mieux que n’importe quel autre que j’ai déjà vu ». Également il est le « meilleur performer de l'histoire du rock n’ roll», avec peut-être Elvis P., qu’il cite principalement pour des raisons « sentimentales ». Mike Appel offre guère de contraste quand il revendique être le manager « du plus grand artiste aujourd'hui au monde, point », un point de vue qu'il ponctue en frappant de son poing droit la paume de sa main gauche. Appel est une curiosité même au sein des managers de rock and roll. John Hammond, le découvreur de talent de la Columbia qui a signé Springsteen, le décrit comme « grossier comme aucun homme que j'ai jamais rencontré », une référence, certainement, aux débordements et parfois aux absurdes pulsions d'Appel pour le conflit. La plupart du temps c'est la presse qui fait sortir Appel de ses gonds, et ça, il se fait que ce n'est pas par hasard. « J'aime faire des choses avec honnêteté », souligne t’il, « et puisque les médias ne sont pas résolus à être honnêtes mais à arriver à leurs propres fins, mon idée sur la façon dont les choses devraient être faites et leur idée sur la façon dont les choses devraient être faites s’affrontent. Alors ce qui se produit est que je suis le gars sur lequel ils concentrent toute leur haine. » Les excès d'Appel et de Landau se retrouvent chez pratiquement tout le monde dans le cercle intime de Springsteen. Peter Philbin. Le responsable de la presse internationale de Columbia, basé à New York, est capable de vanter son client avec une ferveur qui s’apparente à du délire et lors des récents concerts de Springsteen au Roxy à Hollywood il n’était pas tant l’intermédiaire passionné qu’un fou perché sur sa chaise hurlant à se faire exploser la tête. MÊME au sein de son groupe, il y a un respect, presque religieux, respect pour l'homme qu'ils appellent le patron. Clarence Clemons, le saxophoniste âgé de 33 ans, voit sa rencontre avec Springsteen comme pas moins que divinement-façonnée : « Bruce est la personne la plus formidable que j'ai jamais rencontrée, » dit il. « Il est la personne la plus forte que j'ai jamais rencontrée. Quand je l'ai rencontré la première fois il était comme dans la bible où ce type a rencontré ce type et il lui dit « Laisse tout ce que tu as et suis moi » et c'est exactement ce que j’ai ressenti, mec. Mais je ne l'ai pas fait. Et je me suis puni moi même. Et je pense que Dieu m'a puni parce que j'ai eu cet accident de voiture et j'ai presque été tué et toute cette merde. Quoi qu'il en soit. Il est revenu (de Californie où il avait visité ses parents) et nous nous sommes réunis et sommes restés ensemble. » La contribution de Time et de Newsweek à la légende galopante de Springsteen n’en a pas moins été extraordinaire tout comme la facilité apparente avec laquelle Appel a été capable de manipuler ces deux géants indéboulonnables. Time avait précédemment publié un sujet sur Springsteen dans son numéro d'avril 1974. Puis quelques semaines après Newsweek prit contact par ses propres moyens et Time flairant la trace fraîche est revenu à la charge pour une seconde tentative. (Le renouveau d'intérêt avait probablement été stimulé par les dates de Springsteen en août au Bottom Line de New York, duquel naquit l’excessif Bruce-Est-De-Loin-La Personne-La plus Importante A l’Echelle de la Planète actuellement.) Cette fois, Appel expliqua que les règles avaient été sensiblement modifiées. Le jeu était maintenant « Tu me donnes une couverture. Je te donne une interview ». « … et ils doivent te détester pour ça, » dit il. « Ils disent nous sommes New Musical Express, nous sommes Melody Maker, nous sommes Newsweek, nous sommes Time magazine et nom de Dieu qui êtes vous pour nous dire que ça doit faire une première page. Mais je vous dis « que je vous donne la chose la plus convoitée que je puisse vous donner. Je vous donne une interview avec Bruce Springsteen. Je ne peux pas vous donner plus». » Les deux indéboulonnables s’en retournèrent et le résultat net fut cette double couverture de une le 27 octobre (l'anniversaire d'Appel). Le premier artiste depuis Liza Minelli à l’époque de Cabaret. Les deux articles étaient étrangement objectifs considérant l’importance qu'ils attachaient à leur sujet. De nombreuses données biographiques, un soupçon du plus austère genre d’exaltation – dans le cas de Newsweek - quelques infimes sous-entendus comme quoi Springsteen pourrait bien, après tout, être l’un des plus grands matraquages de l’industrie du disque qui, par la loi de cause à effet médiatique, les rendraient victimes, eux mêmes et Time. Il y a quelques années les deux se seraient majestueusement fendus d’une page jusqu'à ce que la légende de Springsteen les bouscule, puis ils se seraient sacrifiés au rite des premières pages. Actuellement, même Time et Newsweek ont peur de passer à côté la toute nouvelle sensation américaine même si cela signifie faire la queue au mauvais théâtre avant que la caisse n’ouvre. « C’est de la folie » dit Springsteen. « Ca n’a pas de sens et je n'attache pas trop d’importance au fait d’être en couverture. Ce n'est qu’un magazine. Ca fait le tour du monde mais vraiment… tu sais. »

« Ca n'a pas grand-chose à voir avec ce que je fais, » dit il. « Je ne pense pas. La raison principale pour laquelle je l’ai fait… tu vois c’est quelque choses que je voulais. Je voulais que Born To Run soit un hit. Pas pour le fric mais parce que j'ai vraiment cru énormément en la chanson et je voulais juste l'entendre sur la radio, tu sais. Sur les ondes courtes. À travers tout le pays. Pour moi c’est la place où devrait être une chanson. « Et ils ont dit, bon si tu as ta photo sur Time, les directeurs de programme pourraient bien réfléchir à deux fois avant de le passer ou de le jeter. Ainsi la seule raison matérielle pour laquelle j'étais sur cette chose c’était exactement pour cette raison, tu sais. Autrement, mec, je le regretterai probablement, tu sais ». Rolling Stone a joué un jeu autrement plus détaché. Toujours opportunistes et à se distinguer par leur exclusivité sur Patty Hearst, leur choix a été de considérer Springsteen comme un de ces phénomènes parmi d’autres de la Côte Est, du genre qui va et qui vient avec la marée de l’Atlantique. Et Playboy … Appel a également essayé de soutirer une couverture à Playboy mais a été informé que le Big Bunny préfèrerait crever que de créer ce genre de précédent. ET AINSI c’est au Roxy à Hollywood que l'entourage de Springsteen est venu du 16 au 19 octobre pour démystifier le battage, parjure et théories associées et c’était avec bruit et peu de cas pour les subtilités convenues que CBS s'est attelé à la tâche. Ils ont commencé par réserver 50 pour cent de la salle la première soirée et on continué jusqu'à ce que le type ordinaire de la rue ait besoin de l’appui des troupes terrestres et aéroportées pour entrer dans la place. En forme de consolation, une flopée des plus grandes bêtes de scène d’Hollywood donnèrent un coup de main… une file qui en fin de semaine comprenait Jack Nicholson. G. Harrison, Jackson Browne, Neil Diamond. Jackie De Shannon (présentée en coulisses), Carole King(présentée en coulisses), Joni Mitchell (partie tôt), Cher et Greg (deux fois), Tom Waits (venu en stop de son propre concert à 140 kilomètre de là), Dick Carpenter(« John, une Marguerita ! ») Wolfman Jack (?) et Warren Beatty.

Le premier soir on assista aux habituelles allées et venues d’avant spectacle ; la décontraction de mise, étreintes Hollywoodiennes, cris à travers les tables et explications sur la vrai cause et à la nature du phénomène Springsteen, et lorsque Bruce finalement monta sur scène chacun fut si soulagé de ne plus avoir à manifester un ennui mortel que le lieu s'embrasa de cris et hurlements qui ont du à moitié le glacer. Il se dirige droit au centre de la scène, qui est sombre, vide et presque angoissante s’il n’y avait pas les cris continuels, il appuie sa tête et son corps contre le pied de micro et juste pour exacerber un peu plus ces comparaisons avec Dylan sort un harmonica pour l’ouverture de « Thunder Road ». Il porte une veste en cuir élimée, une paire de Levis bleu serrés. Il est petit, il est mince et son jeu d’harmonica est aussi minimal que celui de Dylan.

The Screen door slams Un prélude à une chanson à propos d'une pauvre fille qui attend que son King Kong se pointe et mette un sens à ses rêves et Springsteen comme le type dit « Tant pis, les choses pourrait bien ne pas être si parfaites là bas mais qu’importe sautons dans un vieux break et faisons un tour sur Thunder Road ». Hey I know it's late we can make it if we run il y a juste un piano qui accompagne et la voix éraillée et désaccordée … et fatiguée de Springsteen. La tête inclinée. Brando, dans « The Men», lorsque sa copine lui dit qu’elle l'aimera pour toujours même si ses jambes ne le portent plus. En fait, tout cela est assez gênant. Et avec les gens qui circulent dans la salle «ouais… c’est certain que tu sais faire sonner une guitare, Bruce », vous vous sentez un peu de manière inquiétante en dehors du coup. Puis le groupe fait son entrée pour « Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out», également tiré de « Born To Run », et les lumières clignotent et Springsteen commence à ranimer et redresser son corps, essayant de donner un semblant de poids à ce qui sur le disque est un passage assez anodin. Chargé, textes denses. Une mélodie et un arrangement qui sont un patchwork des accents des plus discutables du R n’ R du début des années 60. « Spirit In The Night» est parmi ses mélodies les plus enthousiasmantes, bien qu’elle tende trop fortement vers Van Morrison. Une chanson des débuts tirée de « Greetings From Asbury Park», une période où Springsteen était rattrapé avec l’éclat de la métaphore qui fait mouche … anges gitans, porteurs de mission et une prépondérance de rimes internes et de vers qui laissent perplexe. Crazy Janey. Wild Billy et tout un groupe roulent vers Greasy Lake « environ un kilomètre en direction du côté sombre de la route quatre vingt huit » où les doigts de Janey s'enroulent autour du « paquet » de l'auteur. La scène d'amour et représentée dans l'obscurité avec Springsteen allongé sur le ventre en travers d’une ligne des tables qui jouxtent la scène. Des filles se frottent à son dos quand il chante « Me and Crazy Jane was making love in the dirt singing our birthday songs ». Puis le groupe reprend et les spots se rallument, Springsteen rejoint la scène et à la salle devient comme folle de plaisir (pour Janey et son amoureux cette nuit). Pour l'ouverture du vieux titre de Manfred Mann, «Pretty Flamingo», Springsteen fournit une explication décousue – un monologue sur les origines qui à mi-voix, à moitié-grogné est une assez bonne interprétation de la littérature de comptoir. Le genre de logorrhée dans lequel Dean excellait. Tout le monde finit par se sentir gêné en présence de ce genre de discours. Plus sordide encore est la manière dont il encadre l'ouverture de « E Street Shuffle ». Là il raconte en long et en large comment lui et le saxophoniste Clemons se sont rencontrés. Il avait joué avec un groupe de R n’ R originaire d'Asbury quand une copine lui dit qu'il devrait descendre au Student Prince et jeter un coup d’œil à l’intérieur sur ce gosse de Springsteen. La manière dont Springsteen le raconte, lui et son guitariste Miami Steve traînant dans la nuit froide et brumeuse quand à travers la fumée ils voient un grand homme venir vers eux. « Ils se cachent dans une embrasure de porte et tombent genoux alors que le grand homme approche. Ils sont effrayés et ils ont froids et ils se préparent à filer quand Clarence tend une main, Springsteen sort pour la serrer. Elles se touchent. Et les étincelles volent sur E street. La magie de Springsteen se trouve justement là… à l'apogée de cette histoire singulière. Sur le mot « étincelle », la scène clignote en rouge, Springsteen marque un arrêt et le groupe reprend avec une précision dans l’attaque qui se produit seulement quand il y a un consensus qui opère. Dorénavant le show est vivant, plus raffiné… une situation qui s’étend presque à la musique elle-même. « Kitty's Back», « Jungleland » et « Rosalita » ont pour elles ce côté brumeux du West Side et bien qu’aucune ne soit un miracle de construction il y a suffisamment de continuité et de mouvement : - et dans le cas du « Kitty's Back, » un passage instrumental intense - pour éclipser les moments discutables. Le groupe, en fait, est étonnamment expert à deviner les intentions à moitié-cachées de Springsteen. D’excellents solos sont à l’avenant sur « Rosalita » et « Kitty's Back »… particulièrement du pianiste Roy Bitten… (NDLT: l'orthographe du nom est erronée) et seul l'organiste Danny Federici dont la tendance est de trop rester dans les aigus, est ici sujet à caution. Juste un rappel ce soir… un morceau d’atmosphère hautement dramatique accompagné à l'accordéon et avec des paroles parfois-chuchotés. « Sandy » est à propos de Bruce, ou quelqu'un qui ressemble beaucoup à Bruce, se préparant lui-même à quitter la vie du boardwalk et cela donne à Springsteen l’opportunité de s'ouvrir sur les habitants vivant d’expédients de ce tableau tout entier. Les voyants, les bikers, serveuses, quelqu'un qui s’appelle Madame Marie, chacun d’eux faisant l’aller-retour entre rien et pas grand chose. Au plan lyrique c’est l'un de ses morceaux plus intéressants, puisque c’est l'un des moments rares où il choisit de dévoiler la désillusion qu’il ressent manifestement pour tout les décors depuis le flipper les restaurants routiers jusqu’aux poubelles ce qui constitue la plupart de ce dont il fait involontairement l’éloge dans sa dernière œuvre. « Born To Run» dit-il, « était sur New York. J'y étais depuis des mois. J’étais avec cette fille et elle arrivait juste du Texas et à nouveau elle a voulu repartir chez elle et elle devenait folle et nous étions dans cette chambre et ça allait de pire en pire. Je rentrerais à la maison et elle dirait « en as-tu marre? Es-ce fini? As-tu fini ? » Et j'ai dit « non, ce n'est pas fini, ce n'est pas fini. Je rentrerais à la maison presqu’en larmes. » « Et j’étais en quelque sorte dans tout ce truc d’être nulle part. Mais en sachant qu’il y a quelque chose quelque part. Ca doit être exactement comme ici. Ca doit être exactement quelque part. »

BORN TO RUN était déjà en préparation depuis huit mois quand Jon Landau (précédemment producteur de MC5 « "Back In The USA" et de deux albums de Livingston Taylor) fut associé au travail. Avec Landau dans l’équipe les choses continuèrent à avancer de manière léthargique, bien que les quatre mois et demi suivants furent consacrés à achever la mise en boîte, en revanche, une démonstration de fougue et d’éclairs. Landau attribue les retards au culte de Springsteen pour le détail : « Il pouvait passer des heures », dit-il, « sur une ligne. Il pouvait dire aux gars attendez, je veux vérifier une ligne et quatre heures plus tard il serait toujours assis là à essayer d'apporter les changements de dernière minute à un vers. » Le tandem s’était rencontré en avril 74 dans un club de Boston appelé le Charlie où le groupe de Springsteen jouait. Dans la vitrine du club figurait un encart d’une critique que Landau venait juste d’écrire pour le Real Paper local – Un article coté A -moins qui traitait des « nombreuses imperfections » de Springsteen et également qu’il le considérait comme candidat potentiel capable de dominer le monde. C'était une nuit froide, Landau se rappelle et il a trouvé Springsteen en T-shirt dans le jardin de derrière, en train de sautiller pendant qu'il lisait la critique. Springsteen lui dit qu'il avait lu mieux mais que l’article était exact, et alors Landau se présenta. Le show qu’il vit cette nuit, il le décrit comme « ahurissant » cependant rien de plus qu’une «ébauche» de ce qui se fait actuellement. Le tandem resta en contact et un mois plus tard Landau passa à la publication avec cette critique survoltée pour laquelle Columbia dépensa plus tard 50.000 dollars en promotion… le fameux « j'ai vu le futur du rock n’ roll et son nom est Bruce Springsteen ». Non pas que CBS n'ait eu besoin d’une bonne dose de rappels a l’ordre avant que les troupes s’alignent dans le sillage de Springsteen/Landau. Le sectarisme au sein de la compagnie était très présent… dû en partie à la « flamboyance d'Appel et à la nature inflexible de son client et aussi parce que Springsteen était un poulain du directeur exécutif « disgracié » Clive Davis. Il y eut même des rapports au sujet d’un prétendu complot selon lequel le mythe de Springsteen aurait été arrangé seulement pour irriter Bob Dylan, qui avait récemment quitté CBS pour un contrat de deux disques avec l’Asylum Company de David Geffen. Appel lui-même concède plus qu’à demi-mot qu'un tel plan ait pu exister. « Quand vous êtes dans le management d’une maison de disque de premier plan » , dit-il, « il y a des jeux de pouvoir. Il y a comment vous ramenez Bob Dylan dans le rang, comment vous ramenez son avocat dans le rang ». « Son avocat arrive et demande la lune… demande des royalties rétroactives sur les albums de Bob Dylan. Demande des montants exorbitants. Toutes sortes de choses. Toutes sortes de frais importants. Et ensuite au moment où les négociations échouent, Clive Davis avait quitté la maison de disques et le monde entier avait les yeux tournés vers Columbia Records et tout le monde les prenait pour cible. Ils étaient très nerveux, très tendus à ce moment précis, essayant de faire leurs preuves. Naturellement ils auraient pu dire, vous savez, dans le feu de l’action, « baisons Bob Dylan, nous allons prendre Bruce Springsteen et l'utiliser et juste montrer à ce type qui commande. Cependant, ça ne fut pas d'être le cas parce que cela nous a pris un bon moment pour faire l’album « Blood On The Tracks» et tout ça nous avait pris de vitesse. Et ils sont parvenus à récupérer Bob. » Le comble parfait de l’ironie lors de cet épisode particulier, fut la demande faite par le magazine Time par le biais de CBS pour obtenir une interview de Bob Dylan à propos de Bruce Springsteen. La demande fut rejetée.

« Ils ont fait l'erreur, » dit il, « Ils ont débarqué avec la grosse artillerie. Je veux dire comment ont-ils pu s'attendre à ce que les personnes avalent quelque chose comme ça? (Les premières annonces de CBS le comparant à Dylan). Et à quel point ils sont capables de sous estimer les gens me sidère. Tout le temps, mec, c’est comme… essayer de trouver de la place, mec. Donnez-moi un peu de putain d’air. Lâchez-moi un peu. J'essayais de dire ces types à la maison de disque, attendez une seconde. Êtes-vous en train d’essayer de me tuer ? » C’était comme une tentative de suicide de leur part. C’était comme si personne n'avait besoin de gagner d’argent. « J'étais dans cette ombre géante, mec, dès le début… et je commence juste à me remettre de cette affaire Dylan : Oh Dieu merci ça semble s’atténuer et je suis à la maison à penser Dieu merci les gens semblent oublier ce mensonge et fuuuuu j'ai vu… . Non ça ne peut être ainsi. « Alors immédiatement j'appelle la société et je dis retirez cette citation. Et c’était comme, l'article de Landau. Et c'était vraiment un bon papier et il représentait beaucoup pour moi mais c’était comme s’ils l’avaient complètement sorti du contexte et le faire mousser et qui va avaler ça? Qui va croire ça? Ca va finir par mettre les gens en rogne. Ca m’emmerde. Quand je lis ça je veux étrangler le type qui a collé cette chose là dedans. C’est comme si vous vouliez tuer ces types pour faire des trucs comme ça. « Ils l’introduisent en toi à tes dépens. Ils l’introduisent subrepticement et ne te disent rien du tout. 'C’est comme le fusil d’un tueur qui arrache huit bras. » C'est ce genre de tactique, tu sais. C'est ce genre de tactique et ils la déclenchent pour eux-mêmes et ils la déclenchent pour moi aussi… « C'est une chose idiote. Ignore-la, tu sais. Ignore tout le truc parce que ça n’a aucun sens. Alors comme je suis toujours à la ramasse parce que non seulement tu dois jouer mais tu dois sortir cette connerie de la tête des gens d'abord. » It was so beautiful, I fell James Dean was back... When I saw James Dean for the first time I fell on the floor. When I saw Bob Dylan for the first time I fell on the floor. When I saw Bruce Springsteen for the first time I fell on the floor : (C’était si beau, je sentis que James Dean était de retour… quand j'ai vu que James Dean pour la première fois je suis tombée par terre. Quand j'ai vu Bob Dylan pour la première fois je suis tombée par terre. Quand j'ai vu Bruce Springsteen pour la première fois je suis tombée par terre) Jackie De Shannon autour d’une tasse de café le matin. « Nan. C’est comme… si tout, tu sais. Tout ce que je fais, aime, je note mes impressions sur les trucs, comme, et ce que je vois, tu sais. C’est comme… mais si tu cherches quelque chose sur lequel compter... si tu fais partie d’un groupe c’est comme... Je ne sais pas. Je ne peux pas vraiment me voir comme ça. » Appel a une interprétation plus subtile de la dialectique du battage-versus-légitimité et cela donne ceci : « Je me dis juste « écoutez les amis (de la presse) sortons de ce Bruce… » Pourquoi vos vanités ont-elles bien pu être piquées, votre ego a pu être contrarié mais arrêtons cette connerie. Le gosse est vraiment bon. Il est vraiment différent. Si vous avez un tant soit peu de talent, vous le reconnaitrez. Si vous n’en avez pas, vous serez écrasé. C’est comme un rouleau compresseur. Nous gagnerons à la fin. Vous n'avez aucune chance contre nous. Vous n'avez aucune chance parce que nous avons raison. Nous sommes d’accord ? ». Appel écrivait des jingles commerciaux. Il était également réserviste chez les marines et s'il devient un peu comme Ed Sullivan qui rencontre Joseph Goebbels c’est en gros la manière dont Springsteen le voit aussi. « C’est comme tu ne peux imposer une attitude aux gens. C‘est comme des conneries. C’est comme des salades. C'est une chose terrible. Tu ne peux pas arriver comme si tu étais important, tu sais. Je ne vais pas rentrer là dedans parce que c'est une chose essentielle qui se déroule. C'est une chose simple. C'est un groupe, tu sais. C'est un groupe de rock et tu ne fais que chantez et écrire des chansons. Appel a réussi à rencontrer Springsteen par le biais d’un complice mutuel de la première heure appelé Tinker. Tinker a commencé en construisant des dragsters en Californie, a déménagé à Nassau où il participé au lancement d’astronautes dans l'espace et a finalement fabriqué des planches de surf dans le New Jersey. Springsteen l'a rencontré dans un bar. Il avait 18 ans et Tinker lui dit qu'il pourrait lui trouver un boulot de guitariste dans le groupe de Janis Joplin. « J'ai fini par vivre chez lui pendant environ un an et demie dans une usine de planche de surf. C'était de la folie là-bas. » La première fois que Springsteen est sorti du New Jersey c’était avec Tinker. Chacun dans le groupe avait économisé une centaine de dollars et pris la route de la Californie dans un break et un pickup Chevy. Springsteen a navigué d’une côte à l’autre au cours des quatre années qui ont suivi avant de réaliser que le meilleur groupe qu'il pourrait jamais avoir l'attendait dans le NJ. En 1970 ou 71 - il ne se rappelle plus - Tinker l'a conduit à New York pour rencontrer Appel et exactement comme dans film de série B, Appel est subjugué par le gamin aux cheveux bouclés et à la guitare sèche et au cours des mois l'a suivi avec le grand découvreur de talent de la grande maison de disque. Springsteen à ce moment est en train de lire le livre d'Anthony Scaduto sur Dylan et est fasciné par la scène où Dylan se lance dans le bureau de John Hammond, joue deux ou trois airs et est signé en vitesse. Alors Springsteen et Appel de tenter leur chance et cela marche une seconde fois. Et cela nous amène à deux albums de peu d’audience suivis par un retour de foi de la Columbia lors du Roxy à Hollywood où à la fin de la semaine Springsteen va être propulsé à un degré qui vous remet à l’esprit la doctrine du rouleau compresseur d'Appel. À ce jour même Walter Yetnikoff, président du groupe Columbia Records, est debout sur sa chaise, animé, peut-être, par l'avalanche de dollars qui s’accumulent dans son imagination. Les gamins aussi - et depuis lors, la classe les spéculateurs - ont adopté un comportement qui rappelle plus que d'une lointaine ressemblance les premières années des Beatles, à la différence près que ces gosses sont plus âgés tout comme Springsteen (26 ans). Mais les années n’ont pas de prise sur le mur de foi de Springsteen tel que codifié par Appel, Landau et Philbin et exprimé, même si de manière hésitante à cette époque, par Brucesteen lui-même. Time et Newsweek y croyaient, et les spéculateurs y croient parce que rien ne peut être cru qui n’est supporté par la volonté impérieuse de la foi inflexible telle que manifestée par les susnommés. Springsteen aurait pu manger un chameau entier, tant qu'il restait persuadé qu’un tel projet n'était pas hors de ses capacités, tant que le chameau y croyait et que le marchant de chameau y croyait… ou que lors changement de tenue du roi personne ne remarque que le roi est gros, jambes nues jusqu'à ce qu'un enfant dise « hé, où est son pantalon » et que tout cette foi s'évanouisse en une fraction de seconde. Etant donné que tôt ou tard quelqu'un lâchera le morceau, l’élément de décision reste si Springsteen a finalement oui ou non de quoi couvrir ses jambes… ce quelque chose qui soit une matière artistique et je suggère l'idée que Springsteen est nu en effet. Qu'il n'est rien de plus qu'un chef de file pour un bon groupe de rock parmi d’autres, compositeur de R'n'B n B point, de la matière qui se révèle un peu en avance par rapport à la moyenne. Les prétendues inclinaisons intellectuelles profondes induisent également en erreur parce que Springsteen a ni l'originalité ni les intentions - politiques ou autre - de Dylan qui le laisse avec un plein sac de punk, maniérisme solitaire dont il est déjà las… d'une situation qui a probablement engendré ces 12 mois ½ de contrariété et d’angoisse qu’a été la réalisation de « Born To Run ». Springsteen a une volonté et un style spectaculaire solide et l'air de l’américain moyen solitaire à qui les types de la bande demandent « comment tu vas, Brucie ? » et Springsteen de grogner et de s’en aller sur la jetée pour rencontrer sa copine qu'il aime d’un empressement fidèle et raffiné par opposition par exemple à Jagger, qui pourrait se réveiller n'importe où et ne pas se rappeler comment il est arrivé là. Et il transpire cette bête sagesse animale qui a fait de Brando et Dean de si attirantes suggestions, - bien que Springsteen essaye de bouleverser cette image avec des prétentions littéraires. Appel, le Landau et Philbin pensent qu'ils doivent protéger et vanter leur poulain autrement il meurt, tandis que Springsteen dit avoir besoin de se protéger des Landau, Appel, Philbin et d’autres pour leur mentalité. Et déjà le mur de la foi commence à se fissurer et dans six mois Springsteen sera soit musicalement oublié, ou plus probablement, un gars qui n’a pas su percer, considéré comme dans la moyenne et portant sur ses épaules le ressentiment des spéculateurs et des types du métier qui après cela se considèrent comme lessivés et dupés. « J'avais l'habitude de me sentir maître de moi en permanence» dit Springsteen, 'mais maintenant je ne suis plus si sûr. »

"Eh, tu veux voir un spectacle de rock? Bruce Springsteen et sa petite amie Karen. Merci à Philippe35! |

BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN says he just writes down his impressions of stuff whereas here in Hollywood, Calif., there are people in from New York who believe otherwise. They tell you things like "Bruce is purity". Bruce cuts through grime in half the time. Bruce is what America has been praying for ever since Dylan fell off his motorbike and Brando got too fat to be in the motorcade any more.

BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN says he just writes down his impressions of stuff whereas here in Hollywood, Calif., there are people in from New York who believe otherwise. They tell you things like "Bruce is purity". Bruce cuts through grime in half the time. Bruce is what America has been praying for ever since Dylan fell off his motorbike and Brando got too fat to be in the motorcade any more.  WE'RE IN a vacant room in the Sunset Marquis, Hollywood. Springsteen's eating a bowl of Rice Crispies. Already he's got on his brown leather jacket and he looks like he hasn't slept in maybe four weeks.

WE'RE IN a vacant room in the Sunset Marquis, Hollywood. Springsteen's eating a bowl of Rice Crispies. Already he's got on his brown leather jacket and he looks like he hasn't slept in maybe four weeks.

SPRINGSTEEN IS bewildered rather than nattered by the machinations on his behalf…the hoops he has to go through for the front pages.

SPRINGSTEEN IS bewildered rather than nattered by the machinations on his behalf…the hoops he has to go through for the front pages.