Bring It All Back Home

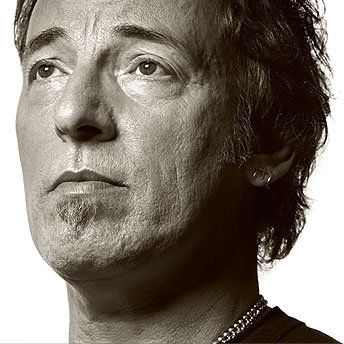

05-02-2009 Rolling Stone par David FrickeThe sound is classic amateur 1966 chaotic, jangling guitars, impatient drumming and crude raging-hormone vocal harmonies and Bruce Springsteen knows every note by heart. Hypnotized by joy in front of a small tabletop stereo cranked to top volume, he dances on the balls of his feet, vigorously strums an imaginary guitar with his right fist and howls along during the chorus "Baby I-I-I-I!" in a deeper wild-bear version of his old plaintive teenage tenor. Springsteen, 59, is happily singing and playing air guitar with himself to "Baby I," a single he made at 16, when he was a guitarist and singer in a New Jersey garage band, the Castiles. Earlier that afternoon, Springsteen is sitting in the wood-paneled living room of Thrill Hill, a 19th-century farmhouse in central New Jersey that he has converted into a studio. He talks about some of the Sixties echoes including the Walker Brothers, Jimmy Webb, the Beach Boys on "Heroes and Villains" and the Byrds' Fifth Dimension ringing throughout his new album with the E Street Band, Working on a Dream. That gets him reminiscing about the Castiles, his first serious band. Suddenly, Springsteen bolts upright in his chair. "I have to dig it out before you go," he says excitedly. "I found the actual two-track tape of our record. I had it put on a CD. It's back at the house. I'll bring it over."

"Well, what could have been a studio back then," Springsteen cracks after he plays both tracks. He and singer-guitarist George Theiss wrote the songs, according to legend, while driving to the session. The band cut them in an hour. "I talk to George once in a while," Springsteen says. "He got married very, very young. Had a lovely family. Made music. I used to see him at the Stone Pony all the time. He had a great voice." But the Castiles' big moment passed that day in '66 their single was never released while Springsteen, nearly 43 years later, is at a new peak in his career. Working on a Dream is Springsteen's third great album with the E Street Band in a decade and arguably the best of the three in its classic-pop songwriting and intimate lyric force. They made most of it on days off from their 2007-08 shows Danny Federici played keyboards on some tracks before his death at 58 last April 17th from melanoma with Springsteen and producer Brendan O'Brien enriching the E Street Band's natural stampede in "My Lucky Day," "What Love Can Do" and the opening eight-minute horse opera, "Outlaw Pete," with an abundance of strings, guitars, choral vocals and saxophonist Clarence Clemons' leonine blowing. The result is Springsteen's most ornate album since 1975's Born to Run. He has already started the new year with a Golden Globe for his theme song to The Wrestler and is assured an Academy Award nomination as well. After his January 18th performance in Washington, D.C., at "We Are One," the free Barack Obama inauguration concert, Springsteen will play a hotly anticipated halftime set with the E Street Band at the Super Bowl on February 1st itself a kickoff for another E Street tour, in the spring in the U.S. and Europe. The last time Springsteen wrote, recorded and hit the road at this velocity was when he was a new Columbia artist. His first two albums, Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J. and The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, were both released in 1973. "At that time, you signed old-fashioned contracts where you were supposed to make an album every six months," Springsteen says. "But after that, I said, 'Nah.' Without going into the whole story" he grins "obviously there was the perfectionism, the self-consciousness and the pursuit of very specific ideas, while you're forming who you are, what you want to write about." Drummer Max Weinberg remembers Springsteen leading endless E Street rehearsals for 1978's Darkness on the Edge of Town and the 1980 double album, The River. "Then, generally, everything we rehearsed would not get recorded we would start rehearsing again in the studio," Weinberg recalls, relaxing on a floppy sofa in a small dressing room at his other job, the Rockefeller Center studios of NBC's Late Night With Conan O'Brien, where he has been the show's bandleader since 1993. "A lot of the tracks on those records were recorded rehearsals. 'Streets of Fire' [on Darkness] it wouldn't even be legitimate to call it a demo. None of us had any idea where it was going." "It was not exciting it was the opposite of exciting," guitarist Steven Van Zandt says of those sessions with a guttural chuckle. One of Springsteen's oldest friends (Weinberg calls him Springsteen's "consigliere"), Van Zandt co-produced those two albums and 1984's Born in the U.S.A. with Springsteen and the singer's manager, Jon Landau. "I'm not that disciplined," Van Zandt admits. "If it's 10 percent less good if we did it in a day instead of a month, I'm cool with that. It's still 110 percent better than what anybody else is doing. Bruce understood that. But he said, 'We're going for 100 percent all the time. We're not compromising one iota.'" "Yes, there was fear of failure," Springsteen concedes, surrounded in the Thrill Hill living room by vintage mounted photographs of what he calls "my saints," including the elder Bob Dylan, the young Elvis Presley and the folk-blues singers Elizabeth Cotten and Mississippi John Hurt. "This is all repair work, in one way or another. The guys I was interested in Dylan, Hank Williams, Frank Sinatra, Bob Marley, John Lydon, Joe Strummer all had something eating at them. Those are the forces you're playing with. And you're in the studio trying to figure out, 'How do I live with myself?' "I'm not worried now about who I am," he says. "My identity, what people are connecting with those things are set pretty firmly. I have an audience, of some kind. I also have a world of characters and ideas I have addressed for a long time. By now, at my age, those things aren't supposed to inhibit you. They are supposed to free you." Springsteen goes quiet for a minute when asked if, even at 16, he had bigger dreams and a stronger will than the other guys in the Castiles. "We were kids, you know," he says. There is another pause. "A lot of it has to do with raw need, motivation. I was very isolated. That's a common story with rock musicians. We all feel like that. And it makes you mad." He smiles, then explodes with laughter. "I mean, really mad! But if you learn to organize your desires and demands and shoot them into something that is more than just being about you, you start to communicate. I wanted to be a part of the world around me." Springsteen had a long-term advantage: the E Street Band, started in 1972, formally named in 1974, reunited in 1999 after a 10-year split and now numbering eight, including bassist Garry Tallent, an original member with Clemons and Federici; pianist Roy Bittan, who joined with Weinberg in mid-'74; guitarist Nils Lofgren, first recruited for the Born in the U.S.A. tour; and violinist-singer Soozie Tyrell, who first played on The Rising. (Charlie Giordano played keyboards after Federici's illness forced him to leave the Magic tour in November 2007.) "They are my greatest friendships, my deepest friendships irreplaceable things," Springsteen says. "I'll put The Rising, Magic and the new one against any other three records we've made in a row, as far as sound, depth and purpose, of what they're saying and conveying. It's very satisfying to be able to do that at this point in the road." "It makes you proud to be his friend," Van Zandt declares with another rusty chuckle, "when so many others are, you know, cruisin'." When Springsteen was a young boy, his mother, Adele, sent him off to sleep every night with a story a rhyme about the ranch hand Cowboy Bill. "She would say it to me before I went to bed," Springsteen says. "It was like our good night to each other." He starts the first verse from memory "Of all the hands on the Bar-H Ranch, the bravest was brave Cowboy Bill" but can't remember the rest. "There were other good lines. I gotta find out what they are." Three weeks later, Springsteen sends them in a handwritten fax after his mom recited them again to him over the phone: "He wore tight boots with heels so high, a 10-gallon hat that hid one eye and sheepskin chaps with flaps/He named his pony Golden Arrow, and every day with a clip and a clop he rode into the highest mountaintop." Later in the tale, published in 1950 as "Brave Cowboy Bill" in a Little Golden Book for children, the hero foils a gang of cattle thieves. "At some point, I told Patti my mother would recite this stanza about Cowboy Bill," Springsteen says. "Patti said, 'Outlaw Pete I think that's Cowboy Bill.' I thought, 'Gee, maybe you're right.'" The longest song Springsteen has recorded since "Drive All Night," on The River, "Outlaw Pete" is the life story of a bandit and killer written in campfire-ballad cadence and swamped in spaghetti-Western ambience Springsteen's return to the cinematic-parable scope of his mid-Seventies songs "Jungleland" and "Incident on 57th Street." "Outlaw Pete" was also, at first, his deliberate turn away from the struggle through 9/11 grief on The Rising and his Bush-years outrage on Magic. "I thought, 'I should write a little opera' something fantastic with a cartoon character, like 'Rocky Raccoon,' by the Beatles." Springsteen cracks himself up quoting one of the opening lines: "At six months old, he'd done three months in jail." The ending is not so cute. Pete tries to run from his crimes, vanishing into thin air maybe dead, maybe not. "I decided to follow the character, see what happens to him," Springsteen explains. What he found was terribly familiar. "We all have to reckon with our own history, because history catches up with you. That's what was not happening over the past eight years in the United States that not knowing, the arrogance that led to thousands of people dying and the country having a complete financial nervous breakdown. If you do not reckon with your own history, it eats you. And if you have that level of authority, then it eats us." Most of Working on a Dream takes place far from newspaper headlines, in darkened bedrooms, under starlight. There is ecstasy and pleading, promises made and broken, underneath the bright, clanging guitars and spiking harmonies in "This Life," "Surprise, Surprise" and the erotic fantasy "Queen of the Supermarket." A man and a woman count their time together and their time left in wrinkles and gray hairs in "Kingdom of Days." Springsteen contends he is not the man, and that is not his marriage, in those songs not all the time: "Patti and I have been together for 20 years. 'Kingdom of Days' is something you write after having a long, long life with somebody, where you see how much you've built together. You also see its finiteness, the passing of the day's light on your partner's face." The song "is about taking the fear and terror out of those things." One line in there "And I count my blessings that you're mine for always" could also be interpreted as Springsteen's thank-you to the E Street Band, one of rock's greatest enduring road shows. It is a group that labored relentlessly for him in the Seventies and Eighties, then was forced to accept his decision in 1989 to be a full-time solo artist for the next decade. Clemons was in Japan, playing with Ringo Starr, when he got Springsteen's call. "He says, 'Big Man, it's over,' " Clemons recalls. "I thought he was talking about the Ringo tour, that I had to come back and go to work. He says, 'No, no, it's over. I'm gonna break the band up.' "Although I heard him say it, I knew it wouldn't last," Clemons swears. "Anything this great, that natural, cannot go away." Springsteen acknowledges the Nineties as "a lost period. I didn't do a lot of work. Some people would say I didn't do my best work." He split the E Street Band because "I lost sight. I didn't know what to do next with them." But after the 1999-2000 reunion tour, he says, "the beautiful realization was 'This isn't a phase. This is it.' The trick in keeping bands together," he adds, "is always the same: 'Hey, asshole, the guy standing next to you is more important than you think he is.'" But Springsteen cautions about reading too much into his first-person voice in "Kingdom of Days" and other new songs: "I will steal directly from life." But that life is "things everyone goes through. I'm not interested in the solipsistic approach to songwriting. I don't want to tell you all about me. I want to tell you about you." Weinberg got that lesson the day he auditioned for the E Street Band. His previous band had covered "4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)," from Springsteen's second album. "I asked him, 'Who's Sandy?' " Weinberg says. "I thought it was a letter. He said, 'Who do you think it is?' Ever since I got that answer, I never ask what the lyrics mean." "This record is a little different," Springsteen says of Working on a Dream. "Its text is not on top, as in The Rising or Magic, where you can immediately connect to the events of the day." In fact, Springsteen did not appreciate the real politics in the new album's title song until the night of November 4th as he watched the election coverage on television. He wrote "Working on a Dream" over the summer, a couple of months after he publicly endorsed Barack Obama for the presidency, but the lyrics are strictly nonpartisan, like a Pete Seeger work song sweetened with the mid-Sixties Roy Orbison. "That was just the simple idea of effort the ongoing daily effort to build something," Springsteen explains, "and that you can't give up. I write my songs. I go around the world to sing 'em, about a particular place that I have imagined, that I have hopes is real. I don't see that often. A lot of what I see is the opposite less economic justice, democracy eroded. "Then, suddenly, election night," he says with genuine wonder. "Suddenly the place you've been singing about all these years it shows its face. You looked in the crowds, you saw people crying, people who lived and worked in the civil rights era, and you completely understood it's real. It's not just something I dreamed up. It can exist. "I don't have any delusions about whatever power rock musicians have I tend to believe it's relatively little," Springsteen declares flatly. But, he quickly adds, "though it may be little, it is important in its particularness. The first time I recognized the country I lived in, the truest version I ever heard, was when I put on Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited. I went, 'That's it. That's what it feels like.' "All you want," he insists, "is for your voice to be part of the record, at a particular time and place. You try to be on the right side of history. And maybe some other kid will hear that and go, 'Oh, yeah, that sounds like the place I live.'" Danny Federici first played with Springsteen 40 years ago. Actually, it was Federici a classical-trained accordionist from Flemington, New Jersey who hired Springsteen when they initially worked together, in 1969 in the hippie-rock band Child, later renamed Steel Mill. "This skinny guy with long hair and a ratty T-shirt was an incredible guitar player and singer," Federici once said, "so we asked him to join." Federici stayed with Springsteen after the latter started running things and forming his own bands. The organist did not play on Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J. but was back with Springsteen by late 1972, in the earliest, not-yet-named E Street Band with Clemons and Tallent. "Those were real frontier days, some of the most reckless times," Springsteen says fondly. "And Danny was one of the most reckless members of the band. In lieu of any other authority figure, I was trying to manage everything." Springsteen smiles. "Danny didn't like to be managed. "All of those things become part of your relationship," he continues. "Those are the people you make your miracle with. And the love that comes out of it is greater than your animosities, greater than time. It's strange, the way the dead remain among us." The E Street old-timers have plenty of Federici stories, and they love telling them. "He was one of the wildest individuals I ever met, a real crazy guy," says Clemons, who roomed with Federici in the early days. Clemons describes crashing one night with Federici and Springsteen in an attic at the Boston home of the mother of one of their ex-managers. "Bruce and I were talking, on our beds. Suddenly, Danny sat up in his bed, wide awake, said, 'Semicomasomadoma,' and went back to sleep. Bruce and I looked at each other and went, 'What the hell was that?' " When Clemons visited Federici shortly before his death, "I said, 'Danny, tell me, before you go, what was that 'Semicomasomadoma' thing?' " Clemons laughs. "He didn't tell me. It remains a mystery." Federici was "like Dennis the Menace, a kid with no respect for authority, going to do what he wants, no matter what," says Van Zandt, who played in Steel Mill. "Bruce came out of his hotel room once, and Danny was there, dismantling the elevator lights to stick on his organ. Another time, in a bar, we saw him dismantle the speakers in a jukebox he was stealing them for his organ." But Van Zandt says Federici was "an extraordinarily instinctive musician. He couldn't have told you the chords in 'Born to Run.' And he never hit the wrong note. Always did the job." Van Zandt laughs. "He got into trouble on his own time." "Danny was a very curious guy incredibly scientific, extremely clued into technology and astronomy," Weinberg says. He too laughs, noting that Federici was also "very honest. Danny didn't want me to join the band. He told me years later, 'I voted against you.'" Weakened by his illness and treatments, Federici made his final appearance with the E Street Band last year, on March 20th in Indianapolis, playing five songs, including his signature organ feature, "Kitty's Back." On April 22nd, five nights after Federici died, Springsteen opened his show in Tampa, Florida, with a film tribute to his old friend and a version of "Backstreets" without organ and a spotlight shining where Federici should have been. "That was Bruce's way of saying, 'OK, everyone is wondering about our loss,' " says Lofgren. " 'Well, let me show you how bad it is.'" In the living room at Thrill Hill, as the late-afternoon winter sunlight fades outside the windows, Springsteen quotes from the last verse of "The Last Carnival," his tribute to Federici at the end of Working on a Dream: "We'll be riding the train without you tonight/The train that keeps on movin'." "That's just life, and it all goes on without you," he says. "The acknowledgment of time, its effects on a good day, it's a sweetener. It makes every element of the day come to life a little more than it normally would. Because you realize it's finite everything around you, the band, the family. In a not very long period of time, someone else will be living in this house, driving these roads. Somebody may go, 'Hey, Bruce Springsteen used to live there.' And in a little bit longer than that, they ain't gonna be saying that anymore. They're just going to be driving by. "That's the way the cards is played. But in the meanwhile..." Springsteen raises his voice to the preacher-fever pitch with which he promises rock & roll salvation each night onstage. "Oh, there is fun to be had and work to do. The band, in truth, is at its very best. I don't believe there has been any other time in our career when we have played better than we did on the second half of that last tour. If you came to see us with your sign with your favorite song on it, something we hadn't played in 30 years, that night we might play it. The band was on fire. Just the acknowledgment of that finiteness made everybody double down on their commitment." The physical cost of three-hour shows and year-long tours over four decades is high. "We were a MASH unit, with heating pads, ice packs, exercise equipment and masseuses all we needed to physically do it," Lofgren says of the 2008 shows, only part-kidding. The guitarist, 57, recently had both of his hips replaced. Clemons, at 67 the oldest E Street member, has had three hip replacements (one hip was done twice) and underwent knee-replacement surgery on both legs last year. Another complication comes on June 1st, when Conan O'Brien and the Max Weinberg 7 take over The Tonight Show, which is produced in Los Angeles. Springsteen shrugs when asked if he is worried about booking E Street gigs around Weinberg's new cross-country commute and shooting schedule. "All I know is this it's all gonna work out, one way or another," Springsteen says. "If people wanna come out and see the E Street Band, they'll be able to come out and see the E Street Band." "It's a hell of a problem to have in this economy," Weinberg says cheerfully, then tells a story that illustrates how well his two bosses get along: About 10 years ago, a well-known actress on an NBC sitcom (Weinberg doesn't reveal her name) requested a sabbatical from the series to make a movie. NBC said no. Her agent pointed out that Weinberg was allowed to go off for six months at a time to play with Springsteen. "The NBC lawyer thought for a second, then said, 'The next time Bruce Springsteen asks your client to play drums with him, she can do that.' " Weinberg grins, noting that in the NBC legal department, "it is known as the Weinberg-Springsteen Rule." Van Zandt takes credit for coining Springsteen's famous nickname. "In our neighborhood, I was the Boss," says Van Zandt, who played with Springsteen in many pre-E Street Jersey Shore bands and shared an apartment with him for a time. "But when I started calling him the Boss, people paid attention." From the start, Van Zandt says, Springsteen "had his eye on history. He was like, 'This ship is sailing. Are you on board or not?'" Springsteen is not the same bandleader he was in clubs like the Student Prince in Asbury Park or even after he graduated to stadiums in the mid-Eighties. "He's become more masterful, if anything," Bittan claims. "Let's not forget he is singing, playing guitar, jumping around, working the audience, playing to the video cameras, conducting the band. That is a lot of balls in the air at one time and to look natural doing it." Based on the way E Street members describe his method of command, Springsteen is the least verbal no-nonsense bandleader in rock. "He doesn't sit down and say what he expects," Clemons says. "He knows, as a musician, what he's gonna get from everybody. Then we live up to his expectations." The most explicit direction Weinberg ever got was right when he joined the E Street Band. "Drummers have a thing we call 'em high-hat barks," Weinberg explains, "that psst, psst sound. Bruce said, 'I like those.' So I threw them in a lot." But there was no instruction from Springsteen in the studio when Weinberg hit that titanic roll at the end of "Born in the U.S.A." "That was completely visceral. That's what I try to do hook up with whatever Bruce is feeling and give him what he wants, the way I do it." As a band boss, Springsteen is a lot like Neil Young, according to Lofgren, who has performed and recorded with Young periodically since the early Seventies. "They are very hands-off in terms of what you do, as long as it feels right," Lofgren says. "Neil likes to get loose, more reckless. But in general, the theme is, get lost in the music. Stay lost in it until you come up for air at the end of the show. But prepare enough so your instincts are true to the bandleader's vision." For Springsteen, that now includes an urgency do more faster which, he admits, is very different from the tenacious perfectionism of his youth: "Patti said it 'You are in a manic state, running like crazy from, let me think, death itself?' " Springsteen howls with glee. "It's a funny thing to say. But I've got a deadline! And that fire I feel in myself and the band it's a very enjoyable thing. It carries an element of desperateness. It also carries an element of thankfulness. "We are perched at a place where we want to continue on with excellence," Springsteen says proudly. "That's our goal. All the rest of the stuff we're gonna figure it out." A few minutes later, he gets up and races home to get that Castiles tape. |

And he does, rushing home Springsteen, his wife and E

Street singer Patti Scialfa and their three teenage children live

in an 18th-century house just down the road and back.

Springsteen doesn't even bother taking off his bulky winter coat.

He strides into the glassed-in porch where he demos new songs and

made his 2005 solo album, Devils & Dust, hits "play"

and flies back to May 18th, 1966, when the Castiles recorded "Baby

I" and the flip side, "That's What You Get," at Mr. Music Inc., a

studio in nearby Bricktown.

And he does, rushing home Springsteen, his wife and E

Street singer Patti Scialfa and their three teenage children live

in an 18th-century house just down the road and back.

Springsteen doesn't even bother taking off his bulky winter coat.

He strides into the glassed-in porch where he demos new songs and

made his 2005 solo album, Devils & Dust, hits "play"

and flies back to May 18th, 1966, when the Castiles recorded "Baby

I" and the flip side, "That's What You Get," at Mr. Music Inc., a

studio in nearby Bricktown.